Reading list

While the other members of his 1980s gang - Barnes, McEwan, Rushdie and Ishiguro - have all bagged a Booker and other awards, Amis remains relatively trophy-less. So why have the big literary prizes eluded him?

Martin Amis plays snooker exactly as you would expect Martin Amis to play snooker. ‘A flair player, one who relies on natural ability,’ as he self-describes in a 1991 account in Esquire of a match against friend and fellow novelist Julian Barnes, ‘he is inconsistent, foul-tempered, over-ambitious, graceless alike in victory and defeat.’ Still, he hits the ball ‘tremendously hard and with various violent spins’. His nickname? ‘Earthquake Amis’, as opposed to ‘Barometer Barnes’, whose approach is marked by ‘exaggerated, even psychotic caution’. The implied comparison between a writer’s cue-artistry and his prose style is made explicit in the final paragraph, qualified by the assurance that Amis is far better at crafting sentences than sinking snooker balls.

Present here are the familiar Amis notes: superabundant, lightly ironised confidence; snappy generalisations made convincing by sheer force of rhetoric; and the droll checking of a literary rival. (Barometer Barnes might as well be Boring Barnes.) Thirty-two years later, though, a new novel by Earthquake Amis barely registers on the literary Richter scale. When his 2020 novel Inside Story failed to be nominated for the Booker Prize, arts correspondents didn’t even bother to dust down their ‘Amis snubbed’ templates.

The last time he was longlisted was for Yellow Dog, exactly 20 years ago, and before then he was shortlisted in 1991 for his Holocaust novel Time’s Arrow. (Back then, Time’s Arrow was Amis’s first ‘grown-up’ novel: it was the only one of his works admired by Roger Scruton.) After just two Booker nominations in 50 years everyone has, it seems, moved on. The others in his 1980s gang - Barnes, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie and Kazuo Ishiguro - have all bagged a Booker, with Ishiguro sailing into the untouchable waters of the Nobel laureateship in 2017. Only Amis, the one with all that talent, remains trophy-less.

Julian Barnes and Martin Amis

© AlamyYou can tell how much this bothers Amis by the number of times he tells us it doesn’t bother him. In two lengthy footnotes in his memoir Experience, he dismisses the Booker for turning writers into ‘something you can bet on’ and for lacking genuine prestige. I suppose it’s a matter of perspective. As the only Booker judge prepared to bat for Inside Story (sorry I couldn’t do better, Mart), I can attest to the capriciousness of the process. But given Amis is one of the most admired and imitated writers of his generation, his self-pity does irritate. ‘When my first novel won the Somerset Maugham Award I told myself… get used to it. And that never happened again.’

Yet just as romantic failure was the muse of his godfather Philip Larkin, so for Amis it is literary failure. From the start, he has been cursed by his own good fortune. The son of Kingsley Amis was always likely to get his first novel published, as Martin admits. But why didn’t Money, his 1984 satire of the film industry, even get shortlisted for the Booker? (Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot did that year.) Perhaps the judges didn’t take to it; but there are other reasons.

Satire is an inevitably divisive genre and his type of humour, highbrow but low-down, has tended to appeal to a certain, often male, reader of pretty much the same background as the author. In current parlance, he doesn’t just punch up but sideways and down as well - he has no problem mocking people less well-read than him. In Money, the whole joke was having a scumbag narrator who doesn’t read, speaking to us in a hyper-articulate prose style, for nearly 400 pages. Amis would also never win a racial sensitivity award, let’s say. (Until Lionel Asbo, Black characters in his novels are peripheral figures of fear or fun.) And then there are Amis’s women: either sex-pots or spoiled wives, with hardly any interior life. You can see why his work can rub people up the wrong way.

His other issue was writing about a very London world inhabited by the same kind of people who sit on judging panels. Unfair, perhaps, but British prizes tend to attract news from elsewhere - Rushdie’s India, for example, or an England set safely in the past, like Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day or Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending. It’s harder to convince a jury you’re doing something original if it feels like they’re being told what they already know.

Kingsley Amis. © Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy

It also can’t have helped that Kingsley was still writing novels - indeed he would win for The Old Devils in 1986. Famously, when the character ‘Martin Amis’ is asked in Money what it’s like having a writer for a dad, he replies insouciantly: ‘It’s just like taking over the family pub.’ But in the mid-1980s, when Amis was at his peak, it wasn’t clear whether he had quite inherited his father’s mantle.

Money is full of cheeky allusions to famous writers: the Ashbery hotel, a business named Wallace and Eliot, a Nigerian writer called Fenton Akimbo. There is even a riff on Shakespeare’s looks: ‘The beaked and bum-fluffed upper lip, the oafish swelling of the jawline, the granny’s rockpool eyes… Shakespeare looked like shit.’

All good, dirty fun, but claiming intimacy with the big boys can come across as arch as well as artificial. In 1989’s London Fields, the femme fatale Nicola Six, rather implausibly, considers the respective attitudes towards ‘sodomy’ of Beckett, Mailer, Updike, Roth and Naipaul (a sexual ‘black mass’, apparently.) Such citations add to the sense of clubbish privilege, of a charmed circle of writers - all male, of course - that we, the mere readers, should feel lucky to be overhearing. And that’s before we get to Amis’s relaying of the table-talk of his great friend Christopher Hitchens.

Amis, I suspect, senses all this. Hence his forays into serious subjects - nuclear weapons, the Holocaust, cosmology, feminism, jihadism. He may satirise the tendency to reward earnest truth-telling in 1995’s The Information by naming a literary award ‘the Profundity Requital’, but the same striving for depth has often unbalanced his own writing. He never alters his style to suit his subject matter. Whether it’s genocide or gentrification, he applies the same hardcore vividity to sometimes queasy effect.

‘We could scrap all the solemn parts of Dickens’s novels without impairing his status as a writer,’ Amis once wrote, and it’s tempting to apply the same rule to him. His gift is to be scabrously, outrageously funny about a narrow slice of upper/lower-class west London in the late millennium. He lacks the warm-hearted soulfulness of his model Saul Bellow or the primal wound of language-loss that haunts Nabokov. Rather, like Alexander Pope, he is a master of the mock-heroic, armed with verbal relish and moral intelligence, ready to scythe down the Dunces of Ladbroke Grove.

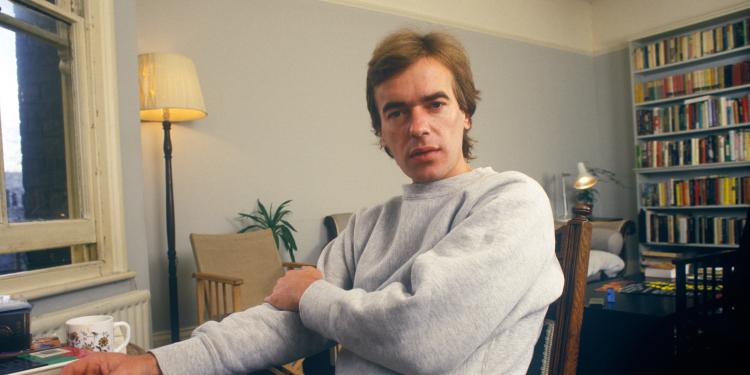

Martin Amis

Courtesy PenguinWhich is why, for me, his best novel is his literary satire The Information. Richard Tull is a failed novelist and failing husband who copes with turning forty by trying to destroy his old friend Gwyn Barry, an effortlessly successful terrible writer. In one memorable scene, Richard and Gwyn play tennis. We observe the ‘hateful remains of Richard’s antique technique, its middle-class severity: the shovelled forehand, the backhand with his heavily lingering slice’ as he tries to scupper Gwyn, a ‘manoeuvrable little hacker taking the pace off everything, always obvious, never contrary, with no instinct to second-guess or wrong-foot.’ If we needed reminding of Amis’s linguistic virtuosity - and it is always worth being reminded - note the two unusual but perfect adjectives, ‘hateful’ and ‘manoeuvrable’. Though I rarely re-read a whole Amis novel, I often drop in on scenes like this to show me what can be done with descriptive writing.

It would be far too simplistic to say that Gwyn is a cipher of Julian Barnes, though he is described with piquant sarcasm as an ‘uxorious’ man - the same word Amis applies to Barnes in Experience, when detailing their falling out over Amis leaving Barnes’s wife Pat Kavanagh, who had been his agent. But, in any case, Amis might claim Barnes threw the first punch.

In his 1991 novel Talking it Over, Barnes presents a love triangle in which the charismatic Oliver betrays his meek best friend Stuart over a woman. Oliver sounds a lot like Amis. Introduced as a chain smoker, he remarks of Stuart’s wedding: ‘The ring glittered on its damson pouffe like some intrauterine device.’ He describes impotence as ‘like trying to ease an oyster into a parking meter,’ an Amis bar line, which he would reclaim four years later in The Information. Friendly teasing? Maybe, though it is startling to read the usually mild-mannered Barnes declare in his account of their snooker match, also in Esquire, that ‘beneath our relaxed admiration for one another’s work lies the… rage to kill.’ (Happily, the pair have now made up.)

Is this anything more than what Updike called ‘higher gossip’? No, and yes. For those interested in male friendship and rivalry, in what success means and what we sacrifice to achieve it, Amis will always have a hold. Especially since his failing characters are not allowed the consolation of being morally superior to those above them in the pecking order. If anything, success makes Gwyn more generous and a better husband, while failure gnaws away at the spiritual core of Richard until there is almost nothing left.

In a perceptive, half-admiring piece on the writer, Jason Cowley writes that an ‘essential loneliness underscores Martin Amis’s quest for absolute originality… What am I worth? How good am I? And one wonders what it has cost him, this relentless striving to be the best?’

Whatever such striving has cost the writer, it has also cost his readers. There was an alternative path for Amis, one that moves beyond mere brilliance. In Experience, the sheer weight of traumatic reality forces him into an attitude of rare humility towards other people. Rather than over-mastering them with his elaborate vocabulary, trapping them with grubby lyricism, he observes and reports with simple acuity.

Amis is reflecting on the devastating revelation that his cousin Lucy Partington, who went missing in 1973, had in fact been abducted and murdered by the serial killer Fred West. His glance at the gruesome life of West is stripped of the yobbish humour so grating in the novels. Instead, he zeros in on a small, telling detail: ‘He would stroll around the house eating an onion like you’d eat an apple.’

Amis has since wondered whether he should even have written about his cousin’s murder. But I’m glad he managed to, as that creepily mysterious onion has stayed with me over the years. It also offers a hint of the writer Amis might have been. If only he had given similar weight to the fictional crimes he describes; abandoned his quickfire certainties; tamed his humorous spirit; if only he had quelled that earthquake imagination…

Martin Amis in 2005

© Barry Lewis/Corbis via Getty Images