Book recommendations

Reading list

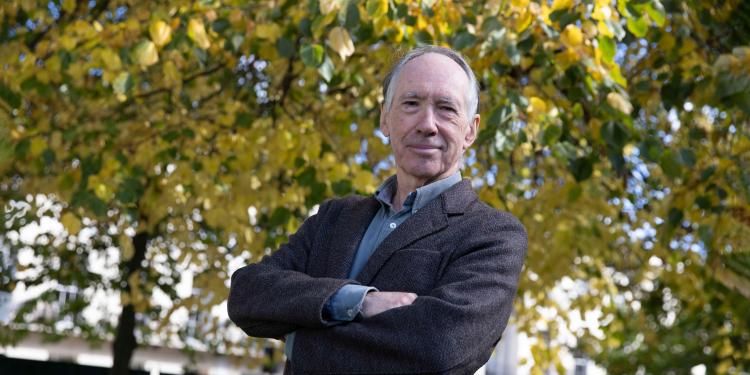

In this exclusive interview, 25 years after winning the Booker for Amsterdam, Ian McEwan revisits his journals and talks about the inspirations behind the book – and the country where he felt like one of the Beatles

Ian McEwan bridles slightly at the description of his Booker Prize-winning novel Amsterdam as part of his ‘middle period’. ‘You can’t have a middle period until someone knows when you’re going to die!’ he laughs.

Yet Amsterdam, which won the Booker in 1998, does lie bang in the middle of McEwan’s stellar career to date. This began almost 50 years ago, with his collection of stories First Love, Last Rites (1975), and has so far produced 16 novels, most recently Lessons (2022). A quarter of a century on, and ahead of McEwan’s 75th birthday this month, it seems like a good time to talk to him about the writing, publication and reception of Amsterdam, as well as its – somewhat controversial – Booker win.

We’re speaking via Zoom, with McEwan in a large, bright room whose walls are layered with bookshelves. This is his Gloucestershire home, and the room is ‘a converted barn. It’s got a door out to a garden and field. It’s a very comfortable place to work.’ He shows me the bookshelves – his working library – the webcam jerkily following his gestures. ‘The books are spread around the house. I’ve never bought a house [that already had] bookshelves in! I’ve bought many houses over a lifetime. Every house I’ve been to, you just think, where are the bookshelves? Where are the books?’

When we first spoke about this interview, McEwan warned he might not remember much about the writing process of Amsterdam. Today, however, he has a solution: he holds up a hardback notebook with a plain navy cover and red binding. ‘I’ve got my 1997 journal here.’ Is this a personal diary? ‘Yes, I’d write in it every three or four days. But looking back now, it’s just amazing, catching the flavour of the time. And I did record quite a lot of my mood… how I was progressing with what I was writing, or how furious I was at myself for not starting. So this journal gave me a pretty clear account.’

Before anyone salivates – as I briefly did – at the prospect of The Diaries of Ian McEwan someday appearing in our bookshops, he adds that ‘I stopped doing these journals in the early 2000s, much to my regret. As I became more and more known there’d been enquiries from libraries asking if they could purchase my journals, and suddenly the innocence began to drain out of them. I had a naive, completely private relationship with the diary. And then the idea that it might be public matter – that ruined everything for me. I just lost interest.’

Amsterdam by Ian McEwan

I was reading a lot of Evelyn Waugh, and I wanted to write something social, elegant, short and comic in the broadest sense

— Ian McEwan

McEwan becoming ‘more and more known’ is part of this story. He had begun his writing career as a succès de scandale, known for his short, shocking stories about tricky subjects: pickled penises, rape, child sexuality. Then came two brief, unforgettable novels – equally immersed in troubling subject matter, from incest to sexual violence – The Cement Garden (1978) and The Comfort of Strangers (1981), with the latter (still one of his strongest works) earning McEwan his first Booker shortlisting.

He then broadened his reach, with The Child in Time (1987), The Innocent (1990) and Black Dogs (1992), which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. They looked out at the world, whereas the early novels had been self-contained and claustrophobic, but throughout the theme remained - of bad things happening to people, only some of whom deserved it. These novels engaged deeply with big subjects – good and evil, innocence and experience – and each release was a bigger event than the one before. Then, in 1997, came Enduring Love, an apotheosis of everything McEwan had been doing: it had strong action in the opening set-piece of an escaping hot air balloon, a frightening antagonist, and playful elements in the novel’s appendix of a fictional research paper.

It wasn’t just readers who were pleased. ‘I’d been very excited and happy writing Enduring Love,’ McEwan tells me. ‘And that’s the only time in my life, and I just loved it.’ Indeed, he enjoyed the process so much that he felt ‘bereft’ when he’d finished it. ‘I felt hugely oppressed at not having a novel to write. I just wanted to be deep into something else.’ But what that meant was getting away from the meaty novels that had become his speciality in the previous decade.

‘What the journal shows is that I had grown desperate to escape what I would loosely call the novel of ideas. Enduring Love was packed with characters saying things that either were me or that I disagreed with, but it had a lot of ideas floating around, and so did Black Dogs and The Innocent.’

The inspiration for Amsterdam was twofold. First, it had to be comic. He was reading a lot of Evelyn Waugh – in particular the story collection Work Suspended. ‘And I wanted to write something social, elegant, short, comic in the broadest sense.’ It’s worth noting that, despite their grim subject matter, McEwan’s earlier novels did have comic elements – for example in The Innocent, where the hero spends a lot of time trying to dispose of a pair of suitcases. ‘It always seemed to me funny,’ agrees McEwan, ‘but no one found it!’

Ian McEwan makes a speech on winning the 1998 Booker Prize for his novel Amsterdam

© Courtesy Oxford Brookes ArchiveThen there was the inspiration for the plot, which winds up over the course of the novel like a clockwork spring, before the contained energy is dramatically released. Two old friends, Clive Linley, a composer, and Vernon Halliday, a newspaper editor, meet at the funeral of a former love, Molly Lane. (The comedy is as blackly McEwan-esque as we could hope: even in the opening pages, there’s a brio to the description of Molly’s unspecified illness, its ‘episodes of ineffectual violence and muffled shrieking’.)

Molly’s death reminds Clive and Vernon of a pact they made some years earlier, which was based on a conversation McEwan had with a friend, the neuroscientist Ray Dolan, while hiking in the Lake District. ‘We were talking about that difficulty that if you have Alzheimer’s you might want to kill yourself – but then you’ve crossed the line and it’s too late. So you might want to make an arrangement for someone else to do you in! And so we jokingly said, “Well, maybe you and I can come to some arrangement on this”. And the code for this was Amsterdam, where there’s a bit of legal euthanasia.’ This then became a running joke between Dolan and McEwan: if one of them forgot someone’s name, or misplaced their car keys, the other would say, ‘Well, it’s Amsterdam for you!’

In the novel, the dark farce of a euthanasia pact is played out against a background of tabloid newspapers reporting government sex scandals. The book was brewing in the dying days of the 1992-97 Conservative government, when Prime Minister John Major’s ‘back to basics’ mantra for moral values left his party open to claims of hypocrisy when its ministers were found to be misbehaving sexually. ‘I thought it had a great deal of opportunity for comedy,’ says McEwan. ‘It became a field day for finding a minister in bed with the wrong person.’

Speaking of which, it’s worth pausing to consider one aspect of Julian Garmony, the government minister in the novel who’s threatened with exposure by Vernon’s paper. McEwan wrote the novel in Oxford, ‘between houses’. ‘There was turmoil in my life because of divorce. I’d been staying in this little flat, and there were nice neighbours - who had a curious surname that I borrowed for the book - called Garmony.’ They were surprised to find their name in an Ian McEwan novel, where, as noted above, bad things tend to happen to people: Garmony in the book finds himself ensnared in a sex scandal. ‘When the book came out, I think they were very upset … but I just wanted a lovely unusual name! And somehow I was never able to put that right for them. They moved away and I never saw them again. I always feel a bit sad about that.’

The book features many scenes, vividly rendered, of the chaos of a newsroom. McEwan is famous for his research, so how did that come about? Unlike his friends Martin Amis and Julian Barnes, McEwan never did time at the coalface of journalism (if that’s the right descriptor for the books pages of the New Statesman). ‘1997 was the year I married Annalena [McAfee], who worked at the Financial Times and then the Guardian. Newspaper newsrooms, especially in those days, were still noisy places – now they’re just like funeral parlours – but it meant that every day Annalena came home full of stories: gossip and intrigue, powerplay and office politics. So I was getting a lot of that and really enjoying them.’ He also ‘blagged’ his way into a couple of news conferences. ‘I think it was the Observer. And that led to the story at the time that I based it all on the Observer, which is not the case.’

In other words – from the newspaper details to the sex scandals – ‘the novel got written out of a lot of things that were just in the air, and in my life.’ This is the sense that Amsterdam gives, rereading it 25 years later: of something free and open, alighting on things already there rather than forcing them out. It’s this that gives the book its lightness, as well as the fact that its pace reflects its composition. After ‘a number of false starts’, he wrote the novel ‘in two very, very intense bursts’, McEwan says, consulting his journal again.

Julian Barnes and Martin Amis

© AlamyDan [Franklin, McEwan’s publisher at the time] said he always knew it was going to win the Booker, but it didn’t even cross my mind. For me, the Booker is a spinning bottle

— Ian McEwan

Moreover, he emphasises, he couldn’t have written his next novel Atonement (2001) – the novel that saw McEwan enter what we might call his imperial phase – without Amsterdam. ‘It somehow cleared the decks and opened up the mental space for me to write Atonement. I know the two books are entirely different. And I know that other people say to me, “Oh, you shouldn’t have won for Amsterdam, you should have won it for Atonement”, but I don’t think I could have written Atonement without first writing this less ambitious, small, almost jeu d’esprit kind of novel. It sort of liberated me.’

He continues: ‘The Innocent and Black Dogs and Enduring Love grew out of wanting to dramatise certain ideas. Whereas with Amsterdam, I just let the scenes flow. Kept my thumb off the scales.’ Well, almost. McEwan – a music buff – admits he gave composer Clive in the book ‘all my scepticism’ about atonal music. ‘I had actually been a concert in South London, which consisted of a man beating the legs of his piano with a baseball bat, to a tiny audience of probably relatives and close friends, all nodding in solemn respect for this absolute absurdity.’

McEwan describing Amsterdam as a ‘small’ book reminds me that it’s a relatively short one – but this isn’t unusual for him. From early novels, The Cement Garden and The Comfort of Strangers, to recent ones such as The Children Act and Nutshell, he has often written at this compact length. Is this a sweet spot for him?

‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘I love novellas, I love reading them, and sometimes I get the urge to write one. They can have a powerful effect. Look at Kafka. Metamorphosis – 16,000 words, yet it takes up a lot of space in people’s thoughts. I remember having this conversation with Julian Barnes, and we agreed that the novella is the form of old age.’ Well, Barnes has stuck to that, I say. ‘He has! Yeah, he says I’ve broken ranks.’

Back to Amsterdam, and its Booker win. Was he surprised? ‘Dan [Franklin, McEwan’s publisher at the time] said, “I always knew it was going to win the Booker”, but it didn’t even cross my mind. For me, the Booker is a spinning bottle. And Julian’s joke about “posh bingo” – which of course he retracted once he’d won [in 2011, for The Sense of an Ending] – holds a lot of truth, because what you know for sure is a different committee would choose a different set of books.’

It’s fair to say that there was a bit of backlash to Amsterdam’s win, even though it had been well received critically. ‘It was very well received,’ McEwan agrees, ‘until it won. Then it really got pissed on, I can tell you!’ Why? Did people make the mistake of comparing it to McEwan’s other, more substantial novels, rather than comparing it to the other entries on the 1998 shortlist? (Douglas Hurd, chair of the judges, described it as a ‘quiet year’ with ‘no sensational or overpowering entries’.) ‘I don’t know. Everyone said the other contestant was Beryl Bainbridge [who was shortlisted for Master Georgie]. She’d built up this reputation of being the bridesmaid, and I would have been very happy if she’d won.’

How did winning the Booker Prize affect him? ‘I’ve been asked many, many times how winning the Booker changed my life. And I don’t want to be rude about the Booker – I just want to say it didn’t change my life at all. Except I certainly had a large sum of money. Delicious, wonderful.’

Winning, though, must surely have scratched an itch, after being shortlisted twice before? ‘Yeah. It’s good to get it out of the way. I mean, Martin [Amis] never won it; I think he was shortlisted once in his life.’ (In 1991, for Time’s Arrow; he was also longlisted in 2003 for Yellow Dog.)

Yet it remains the case that it was after McEwan’s Booker win in 1998 that his next novels – Atonement (2001), Saturday (2005) and On Chesil Beach (2007), all of which were long- or shortlisted for the Booker Prize – made him the most famous and celebrated literary novelist in the UK. Perhaps this wouldn’t have happened to the same extent, or at the same pace, without the Booker win.

And what about other countries? I ask him before we end our conversation. Is there anywhere else in the world where he has the same status that he enjoys in the UK? ‘Germany, definitely,’ he says quickly. ‘And China. I went to China in 2017 and it was like being a Beatle! The Chinese are very in-your-face, they’re not shy. Sometimes I have to be bundled into a car!

‘One time just before I was giving a reading,’ he concludes, ‘I went to the bathroom and was peeing in a urinal. And I was aware of someone standing beside me… And suddenly this book and a pen slid across. I nearly lost it! I shouted [an expletive] very loudly, and a security guard came running in.’ Perhaps it is not too late for that over-zealous fan to find his way into a future Ian McEwan novel – a dubious honour, to be sure: we all know what happens to characters in Ian McEwan novels.

Kiera Knightley and James McAvoy in Atonement.

© WORKING TITLE / Allstar Picture Library Ltd. / Alamy Stock PhotoWinner The Booker Prize 1998