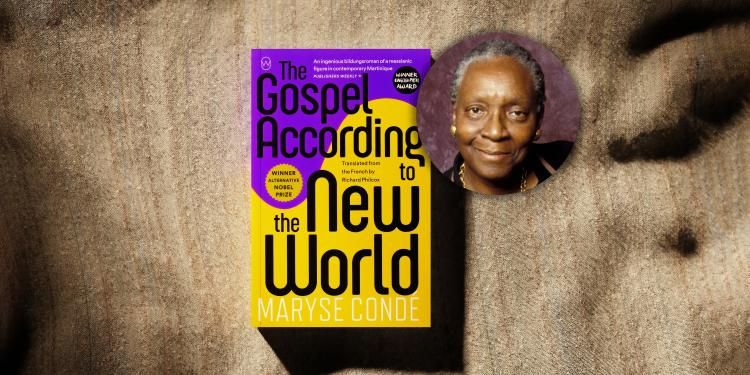

Richard Philcox interview: ‘A translation can be a work of literature on its own’

Shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, translator Richard Philcox talks about The Gospel According to the New World in an exclusive interview

With The Gospel According to the New World shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023, the author talks about becoming ‘intimate enemies’ with her translator husband – and the writers who have inspired her

Read interviews with all of the International Booker Prize 2023 authors and translators here.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023 and what would winning mean to you?

This is the second time I have been listed for the International Booker Prize and I am grateful that my novels can be made available to an English-speaking audience. Winning would be a way of celebrating my latest and final novel The Gospel According to the New World.

What were the inspirations behind the book and what made you want to tell this particular story?

My mother was a devoted believer and my father a confessed atheist and an ardent critic of my mother’s religious beliefs. I wanted to translate this dichotomy in my novel into humour and irony, but I didn’t have the courage until I read José Saramago’s The Gospel according to Jesus Christ and the South African author J.M. Coetzee’s trilogy on the same subject.

How long did it take to write the book and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts or sudden bursts of activity? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

It took me roughly a year and because of my loss of vision I had to dictate the text to a friend as well as my husband. This obliged me to write each chapter in my head. I was sensitive to sound and meaning because the writer is also a musician. The process was delicate and complex. I endeavored to give to the person I was dictating to the version I had written out in my head.

Where do you write? What does your working space look like?

I prefer to dictate my thoughts in the afternoon after I have developed them in my head during the morning. Before I lost my eyesight I used to work very early in the morning at my desk on my computer in Guadeloupe with a view of the volcano, La Soufrière.

Maryse Condé

© P. Matsas Leemage- Hollandse HoogteBefore I lost my eyesight I used to work very early in the morning at my desk in Guadeloupe with a view of the volcano, La Soufrière

What was the experience working with the book’s translator, Richard Philcox, like, given that he also happens to be your husband? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Did you offer any specific guidance or advice? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration or joyful moments or challenges?

I have often said that working with my husband and translator, we become intimate enemies. For me, I feel dispossessed of my work when it is translated, but I confess that I am always excited to be introduced to the English-speaking world. We both work apart, except for Richard’s occasional questions, and I feel confident that his translation is a faithful mirror of the French text.

Why do you feel it’s important for us to celebrate translated fiction?

Because translation has always been treated like a poor cousin and needs to be recognised in the literary landscape. The International Booker Prize is ‘the royal road to cross-cultural understanding and literary enrichment’, if I may quote from Mark Polizotti’s Sympathy for the Traitor: A Translation Manifesto.

If you had to choose three works of fiction which have inspired your career the most, what would they be and why?

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë, because she touched my heart and mind when I was a child in Guadeloupe thus proving the force and magic of literature. Consequently, I adapted it into a Caribbean setting under the title La Migration des coeurs in French and Windward Heights in English.

Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy, for the same reasons as above.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, because it was the first book I read on the ravages of colonisation.

Richard Philcox