Book recommendations

Reading list

Under attack from within, Lia tries to keep the landscapes of her past, her present and her body separate. But time and bodies are porous, and unpredictable. Read the opening words here

Something gleeful and malign is moving in Lia’s body. It shape-shifts down the banks of her canals, leaks through her tissue, nooks and nodes. It taps her trachea like the bones of a xylophone. It’s spreading.

Lia’s story is told, in part, by the very thing that’s killing her; a malevolent voice that wanders her systems, learning her from the inside-out. The novel moves between her past and her present as we come to understand the people that have shaped her life.

In turn, each of these take up their place in the battle raging within Lia’s body, at the centre of which dances the murderous narrator and a boy nicknamed ‘Red’ - the toxic chemo that is Lia’s last hope.

Read more extracts from this year’s longlisted titles here.

Read an interview with Maddie Mortimer here.

I, itch of ink, think of thing, plucked open at her start; no bigger than a capillary, no wiser than a cantaloupe, and quite optimistic about what my life would come to look like. I have since ached along her edges. Delighting in my bare-feet-floorboard-creeps across from where she once would feed, down to where her body brews, I have sampled, splintered, leaked and chewed through tissue, nook, bone, crease and node so much, so well, so tough, now, that the place feels like my own.

It is, perhaps, inevitable that after all this time, I have come to feel a little dissatisfied with the fact of my existence. This is not easy to admit. I suppose one can only be a disaster tourist for so long before the cruel old ennui starts to set in. But the Greeks said that in the beginning, there was boredom. The gods moulded mankind from its black, lifeless crust and this is, of course, encouraging.

Today I might trace the rungs of her larynx or tap at her trachea like the bones of a xylophone or cook up or undo some great horrors of my own because here is the thing about bodies: they are impossibly easy to prowl, without anyone suspecting a thing.

Until, of course, they do. And then, of course,

they aren’t.

Maddie Mortimer

© Ben MankinLia remembered two things about the beginning of the end.

The first: the time it took the traffic lights to change.

The second: the fact that nobody died.

She was one crossing away from the place she needed to be, the surging rhythm of the city in her pulse, the day tripping quick towards rush hour. Her senses felt unusually alert. Nicked wide open by nerves, perhaps. It was nice. A nice change. To feel this exposed, this alive, whilst standing at a red light waiting for the world to resume itself.

A man in a suit that was too small for him sighed heavily and hailed a taxi.

Two women spoke loudly on their phones, slices of their conversation burying themselves into the back of her neck; I told him I said you can’t help how you feel. Booked the two thirty slot tomorrow, there’s some leftover casserole in the fridge you can microwave. No cash, I’m afraid. Won’t be late. God, I always feel so bad. Remember to feed the cat.

Lia pinched the velvet of her earlobe and thought about tragedy.

Which poet was it that said an abiding sense of tragedy

can sustain a man through temporary periods of joy?

Which philosopher was it that said

all tragedies begin with

an admirable quiet?

Today had been full of clamour.

Everyone seemed seconds away from catastrophe.

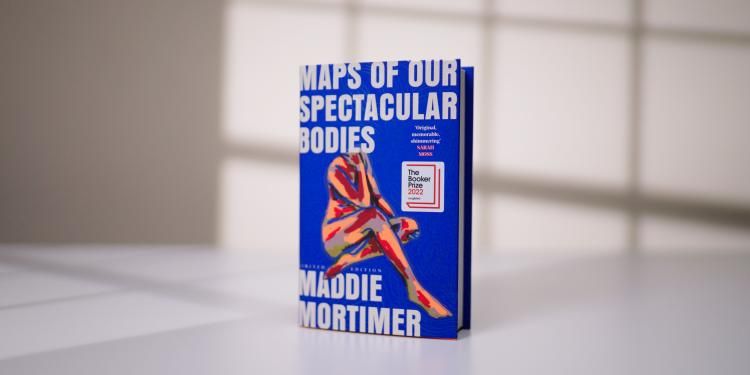

Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer

The city just keeps culling, there is grief on every street, Lia thought, as the plump belly of a toddler emerged at an open window and her eyes flicked down the floors below, counting, jaw tight, as the toddler leant its milk-white head out in delight, resting its tiny fingers on the ledge.

The belt of a woman’s coat bounced against her bicycle spokes. Cycling accidents were rising at a steady rate of 15 per cent each year. More than 4,500 resulting in death or serious injury, yesterday’s newspaper had read. The city just keeps culling, there is grief on every street, Lia thought, as the plump belly of a toddler emerged at an open window and her eyes flicked down the floors below, counting, jaw tight, as the toddler leant its milk-white head out in delight, resting its tiny fingers on the ledge.

Four floors. The fall was four floors down.

Fluorine is pale yellow, chlorine is yellow-green, and bromine is red-brown.

A girl in a blue school uniform began lecturing her friend loudly on the subject of elements.

The halogens get darker as you go down, see.

Lia noticed the girl had thick straight lashes that interlaced as she blinked and a profile of rare, youthful prettiness, the kind that stood out amongst the mass of waiting faces, growing impatient at the crossing, and it was always so hard, she thought – so hard not to get distracted by beautiful things.

Back at the window, the toddler had disappeared. The window had been shut. This was, of course, a relief.

She took a deep, heavy breath in through her nose, concentrating on the stretch of her ribs, the widening of her chest, and held it. Trapped it there. The crackling warmth of petrol air. It had been two years since she’d walked these streets. Crossed this crossing. Two years since she’d sat staring at the scan of her body and brain pinned up against the light, pointing to the dark patch swimming about the centre. That’s the corpus callosum, the doctor had said. Nothing to worry about (she let the long, lovely breath rush through her lips) just the thick nerve tract connecting one hemisphere to the other.

A gap in the traffic had emerged. A clear path, connecting one side of the road to the other. The lights still hadn’t changed. A man with matte skin made a break for it, which prompted the girl in the blue school uniform to dart out into the road too, pulling her friend behind her. It was then that Lia’s eyes latched to the car, turning the corner, coming quickly through the afternoon. She saw the collision before it happened, felt the possibility of it collapse in on her lungs the way rain crescendos into something more than rain.

A throat-screech brake. Delayed smack of machine impact. The buckle of skinny knees as the girl’s body hit the concrete. Lia felt time fold, the seconds doubling over. Oh my God, a telephone voice rasped loudly by her ear, but before she could get a closer look, the scene had flooded with people, all gnawing, clawing away at the prospect of a massacre, quick as starving rats to sudden crumbs.

Lia wanted to be sick.

The girl was dead. She knew it. She could feel it; the new chill in the air, the slowing of the clouds, the dizzying shift of atmosphere when tragedy drops into an ordinary day like this. The crowd seemed to be multiplying and all Lia could think was –

she would never get to tell her parents about the sort of day she’d just had. She would never take a chemistry exam or fall in love or know what a particularly nasty UTI feels like; she would never go to Manchester to study medicine, never become a medic or get to save any lives, and perhaps there would be other people that would die in years to come because of this very moment, because a man with matte skin had made a break for it and a young girl in a blue school uniform who knew things about elements had darted out into a road too soon, and Lia had watched all the glittering possibilities of her life flare up and flicker out, just like that. She imagined the horror of walking over, leaning down with the rest of the rats, pushing the girl’s hair gently off her face, to find that it was Iris, her Iris, her eyes stripped clean of their life.

A perfectly functioning body! the doctor had said. And a happy, healthy brain!

As if there really was such a thing. The crowd had parted a little, so that Lia could finally get a glimpse of the girl lifting to her feet, just as Iris would at three or four, after having taken a tumble. I’m fine, she was saying, as she brushed herself down, quite unharmed. Someone offered to examine her knees. I’m fine, she said again, only louder and harder, her face flushed pink from the shock.

Lia couldn’t believe it. It was, of course, a relief. But also – the slightest bit disappointing.

The girl’s friend led her back to the safety of the pavement, where they both began to laugh, quite hysterically, the terrible sound churning away into the violent city. The spectators dispersed quickly, clumsily, back to their journeys, ashamed of their bloody appetite, and Lia felt the edges of the place cool and settle, her mind collecting up all that had briefly unravelled as the traffic lights went from chlorine to fluorine to bright bromine red, as the world shifted down

three octaves

too late.

By the time she had got to the other side of the road,

she had landed on Yeats.

The poet was Yeats.

She still couldn’t remember the philosopher.

Her eyes remained locked to the pavement until she reached the hospital.

The doctor said it was bad news.

It was back.

She couldn’t hear the rest.

The room had emptied of all sound.

There was only the chilling giggle of the girl who hadn’t died. So faint it was barely audible at first, but as it grew clearer and closer the voice was joined by other voices, those of London’s lucky inhabitants who had all narrowly missed their endings, and like wave strengthening upon wave their lament bounced between the brick and glass of the city before rushing in, at last, through the crack in the hospital window, filling up every inch of the room:

It was you, Lia.

Not us.

You.

Next up, @MaddieMortimer makes the #BookerPrize2022 longlist with ‘Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies’. @picadorbooks @panmacmillan https://t.co/AUrO6nqyhs pic.twitter.com/CKyUHVero6

— The Booker Prizes (@TheBookerPrizes) July 26, 2022

They, seeds of her hope, choir of her heart, now they are all rustling awake.

They, with their histories, plots, songs and remedies, stretch out from the mist-thick blanket of sleep, as word of my little disfigurement carries, like a gut-wind carves and cleanses a day, and

I must admit to feeling a little pleased.

You cannot polish a diamond without a bit of friction, after all, and it is beautiful, really, the way they yawn and twitch, shudder, click, sniff, wet and stiff as dogs smelling ghosts,

ready to try and snuff me right out.

Maps of our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer is published by Picador, £9.99