Empire of the Sun

by J.G. Ballard

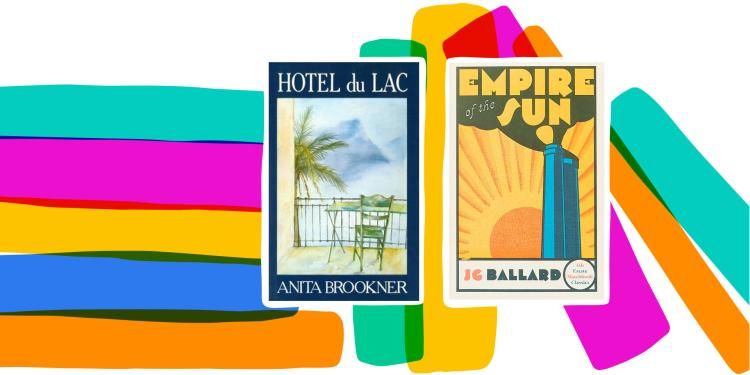

On this episode of The Booker Prize Podcast, our hosts revisit the works of two titans of literature, which were in the running for the 1984 prize, and ask – did the right novel win?

Listen to more episodes from The Booker Prize Podcast here.

In 1984, many assumed that J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun had the Booker Prize in the bag. But actually, it was Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac that clinched the prize in the end. This week, we’re exploring the bookies’ favourite vs the Booker winner to ask which book should have won: Brookner’s short, quiet novel set in a genteel Swiss hotel or Ballard’s long and action-packed autobiographical epic set in wartime Shanghai.

Anita Brookner, 1986

© Peter Jordan/AlamyJ. G. Ballard 1988

© David Levenson/Getty ImagesTranscripts of The Booker Prize Podcast are generated using both speech recognition software and human transcribers, and as a result, may contain errors.

—

Melvyn Bragg:

Well, there’s no doubt that that’s a great surprise to most people here because Ballard seemed such a very clear favourite. Hotel du Lac though, is an excellent book.

Jo Hamya:

Hello, and welcome to The Booker Prize Podcast with me, Jo Hamya.

James Walton:

Me, James Walton. And that clip you just heard was Melvyn Bragg summing up on live TV what had just happened at the Booker Prize ceremony in 1984, the golden age of the comb over, to judge from the footage, as Anita Brookner returned to her seat having picked up the Booker for Hotel du Lac. Melvyn wasn’t wrong to call her win a surprise, or to say that J.G. Ballard’s Empire of the Sun had seemed such a very clear favourite.

The bookie, who appeared at the beginning of Channel 4’s coverage there, I think. Graham Sharpe from William Hill used to show up every year, he put Ballard at 4-7 on. The TV panel of Peter Ackroyd, Malcolm Bradbury, Germaine Greer, and Hermione Lee had all agreed that Ballard should and would win, after which Melvyn summarised by saying, “Ballard, it seems, has it.”

But then, in this fairly low-key announcement of the winner, from Professor Richard Cobb.

Prof. Richard Cobb:

It is the decision of the judges that this year’s Booker McConnell prize should be awarded to Anita Brookner.

James Walton:

And with that, we got a closeup of Anita Brookner’s face. And Jo, have you ever seen a human being looking more stunned?

Jo Hamya:

No, but she recovers very graciously. The bit that I like though is that… Then there are speeches after Brookner’s speech and you just… The camera pans around and you see all these people puffing on cigars looking extremely disgruntled.

James Walton:

Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

All of which makes the 40th anniversary of that 1984 shock perfect for an episode of our occasional the Booker versus the bookies, where we go back to a year where the hot favourite lost and decide who was right. Booker or the bookies?

Should the 1984 judges have gone for Anita Brookner’s short, quiet, novel, Hotel du Lac, set in a genteel Swiss hotel, or J.G Ballard’s long and action-packed autobiographical epic, the Empire of the Sun, set in wartime Shanghai before and after the Japanese invasion?

Also, later a film by Steven Spielberg, which I think James thinks is something unlikely for Hotel du Lac.

James Walton:

Yeah, I can’t imagine Spielberg making a film of Hotel du Lac. It was a well-received BBC three-part series, which suited it.

Jo Hamya:

I suppose it’s more of a Joanna Hogg endeavour. And the Empire of the Sun screenplay, incidentally, it was written by Tom Stoppard. But yeah, it was a year of then quite familiar names on the shortlist, I think.

Flaubert’s Parrot by Julian Barnes, In Custody by Anita Desai, According to Mark by Penelope Lively, and Small World by David Lodge. It’s maybe worth noting because Hotel du Lac is actually quite… I think the panel of TV judges at the ceremony described it as a “quite feminine novel.”

James Walton:

Including Germaine Greer. She wanted it to be a woman’s book.

Jo Hamya:

And Hermione Lee. And something in me slightly baulks at that description. But it is very much a novel about women and a woman’s inner life. It’s worth noting that four of the five judges were men.

James Walton:

Yes, that reminds me of one of my favourite Booker facts actually. In 1986, four of the judges were women for the first time, and still quite rare. And the winner was Kingsley Amis, who’s not often thought of as a great feminist champion.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah.

James Walton:

So yes, at least four male judges and they went for Anita Brookner.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. But with all of that being said, we’re going to go ahead and decide who should have won. Anita Brookner or J.G Ballard?

James Walton:

It’s about time this was decided once and for all, Jo. Probably.

Jo Hamya:

So we’re going to start with the winner. We’ll start with Anita Brookner. James, can you tell us a bit about Brookner?

James Walton:

I can, yeah. I got rather fascinated with her looking into this actually. She died in 2016, I should say. But was born in 1928 in Herne Hill, suburb of South London. Her father was a Jewish immigrant from Poland who’d arrived in England when he was 18, and her mother was a granddaughter of a Jewish immigrant who’d founded a tobacco factory. In fact, where her father worked.

Her mother had also been quite an accomplished singer, I believe, who chose to give up singing when she got married. And Anita Brookner said she was disappointed for the rest of her life. Anita Brookner, clever, very clever. A degree in history at King’s College, London and studied art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London where she was taught by the Courtauld Director, Anthony Blunt, who was also the surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures.

But most famous for later being revealed to have been a Soviet spy. Anyway, Brookner went on to become the first ever female Slade Professor of Art at Cambridge before being invited by Blunt back to the Courtauld, where she taught until her retirement in 1988.

Meanwhile, in 1981, age 53, she published her first novel, A Start in Life. And from then published one every year with Hotel Du Lac, therefore being her fourth. And also, some people have suggested that she essentially wrote the same novel again and again. And one of those people was Anita Brookner.

Her heroines tended to be highly intelligent, rather lonely spinsters in London mansion flats whose lives haven’t turned out the way they hoped. When she died in 2016, there was a lovely piece in The Guardian by Julian Barnes, who met Brookner through that 1984 Booker Prize actually, about the occasional lunches they had, very much on her terms.

Apparently she’d turn up and tell him that she’d just completed a novel and Barnes says, “Dropping her voice to add in a low confidential tone, ‘It’s about a lonely woman.’” A friend of mine reckons that he’s never read a Brookner novel that doesn’t have a scene in which a disappointed spinster scrapes the meal she’s lovingly prepared for some prospective beau into the bin because the beau hasn’t shown up.

And that’s something she went along with really. Interview with the Paris Review, she said, “I’m one of the loneliest women in London.” Someone said she should be in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s loneliest woman. Also, that if she’d been happily married with six children, she may never have written anything.

I always wondered if this was her shtick, but it doesn’t seem to have been. One interviewer asked her, again, “Seriously, did you really actually wish for marriage?” And she said, “Of course. All the time. I wanted children.” But in a way, that’s the great thing about her I think, is that she’s completely unsparing. She refuses to take refuge in the illusions and denial and self-deception that most of us need to get through the average day.

In that piece I mentioned, Julian Barnes also says, “I once went into a London local radio station for an interview, and the team there was still in state of shock from having had Anita in for a very rare appearance the previous day.” He asks why they were in the state of shock. “She answered every question truthfully,” they replied.

And I think that applies to the books too, which cast a completely beady eye over our main characters, and the more flashy, less moral types whose lives are much happier. But while the resulting novels are definitely pretty melancholy, I think they’re also quite funny. Not always flat out funny, though they sometimes are. But certainly witty and amused really. There’s an amused tone in the tragic comedy of it all.

As she once said, “The truth I’m trying to convey, is not a startling one, it’s simply a peeling away of affectation. I use whatever gift I have to get behind the facade. But I hope I’m not an aggressive writer, and that I see through people with compassion and humour.”

But before we decide whether that mission is accomplished in Hotel du Lac, Jo, maybe a little summary of the novel?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, we open up with our protagonist, Edith Hope, who is the author of several quite, I suppose, romantic in scope… I got the impression of Mills and Boons-type novels. Edith writes under the pseudonym Vanessa Wild, initials VW, which I assume is a reference to Virginia Woolf, who Edith has said to look like.

Although, this is at some points contested throughout the book. So at the start she’s on her way to Hotel du Lac in a taxi. We learned that some form of disgrace has come upon her, she’s been sent away by friends.

James Walton:

That’s what’s called an unfortunate lapse.

Jo Hamya:

Yes.

James Walton:

Which we don’t find out about until much later.

Jo Hamya:

So she’s been sent away by friends to this Swiss hotel, which turns out to be quite empty. It’s off-season. It’s full of quite strange characters. There are Mrs. Pusey and her daughter, Jennifer, who are incredibly greedy, rich, quite avaricious women, who seem to spend all their time shopping.

The anorexic Monica, who has been sent to the hotel by her husband to get fattened up so that she can bear children for him. Really, all she does is smoke cigarettes and feed her meals to her dog, Kiki, who is a source of constant frustration to Mr. Huber, the owner of the hotel.

There’s Madame Bonneuil who has been sent to the hotel by her son, she’s hard of hearing. But essentially exiled there because her son’s new wife doesn’t like having her around the house. And there is Mr. Neville, who is a quite strange and forthcoming businessman, who takes an interest in Edith.

She meets all these characters, she talks to them. Often, she goes back to her room and she writes letters to someone called David, who we can safely presume she has been having an affair with. She reminisces about David coming to her house in London after seeing his wife to take a break from family life and enjoy respite.

James Walton:

Yeah, so Jo, we’re getting in the tricky territory now of how much to give away.

Jo Hamya:

Yes, I think it suffices to say that, a late stage in the novel, we come to find out that friend of Edith’s in London before the events of the novel, Penelope Milne, had tried to set Edith up with a quite sensible middle class man called Geoffrey, who promised her all the trappings of married life and societal-

James Walton:

Just lost his mother who he lived with up until that point.

Jo Hamya:

Yes. Gave Edith his mother’s extremely ugly opal ring as an engagement ring. Never a good sign, opal, on an engagement ring. No offence to anyone who has one who’s listening.

James Walton:

And John, I’ll be taking Jo.

Jo Hamya:

And we find out that actually all the while Edith has still been seeing David, who is a married man. On the day of her wedding she jilts Geoffrey, provoking massive amounts of shock from London society, and is sent by Penelope to Hotel du Lac to reflect.

James Walton:

So that’s her unfortunate lapse.

Jo Hamya:

Yes, that’s her unfortunate lapse. At Hotel du Lac, Mr. Neville, who we’ve mentioned before, makes a rather business-like proposition to Edith.

James Walton:

A completely loveless proposal.

Jo Hamya:

Yes. Edith has been reflecting on, I suppose, the moral state of her character in relation to all these strange eccentrics who she’s been coming across. And Mr. Neville tells her that she ought to be more selfish, she ought to have more self-interest and she ought not to rely on love so much in life.

And he tells her, “We could get married and you could go off and do whatever you want. You could keep writing your little novels even though you don’t really have to. You’d be a well-kept woman, and I, by the same token, could go and do whatever I want.”

And so, I suppose, the [foreign language 00:11:26] of the book is Edith deciding whether to return to London having taken up Mr. Neville on his proposal, or to hang on to her love for David.

James Walton:

Yeah, who’s never going to leave his wife or anything, is it? I mean she’s very much a-

Jo Hamya:

Probably not. You have a good joke about mistress, James, don’t you?

James Walton:

A woman who was seeing a married man once told me this rather sad joke, which was, “If your wife and your mistress were drowning, who would you save? And the answer is, ‘You’d save your wife because your mistress would understand.’”

Well, anyway… Yes, and that’s the position she’s in. She talks about all the lonely weekends she’s had and the times that he couldn’t get away from his family, and the holidays they’ve cancelled and everything. So she’s in that classic mistress position.

Jo Hamya:

Yes.

James Walton:

So is she going to return to that or is she going to go off and have this, in a way much more, well, certainly financially fulfilled, probably less lonely life, with Mr. Neville? And that’s the bit we’re not going to give away.

Jo Hamya:

Yes, we won’t. In general, an extremely atmospheric novel with this quite dreamlike setting of an off-season emptied out hotel. One that I suppose meditates a lot on the differences between the sexes and the nature of womanhood, on what expectations women should have out of life.

It’s always very curious to me that it never seems to be an option for Edith to simply, at the end of the novel, return to London alone and have an independent life. But James, did you like it?

James Walton:

I do love this book. Yeah. I mean, you’re talking about the atmosphere. This is a test of whether you find Anita Brookner funny or not. This is early on, she’s talking about this hotel, “As far as the guests were concerned, it took a perverse pride in its very absence of attractions so that any visitor mildly looking for a room would be puzzled and deflected by the sparseness of the terrace, the muted hush of the hop of the lobby, the absence of piped music, public telephones, advertisements for scenic guided tours or notice boards directing onto the amenities of the town.

There was no sauna, no hairdresser, and certainly no glass cases displaying items of jewellery. Its bar was small and dark, and its austerity did not encourage people to linger. It was implied that prolonged drinking, whether for the purposes of business or as a personal indulgence, was not communal foe. And if thought absolutely necessary, to be conducted either in the privacy of one’s suite or in the more popular establishments where such leanings were not unknown.”

So that’s the hotel where she finds herself. And at the risk of another lengthy extract, I’d like to see what you make of what, I’m pretty sure, is the central theme which is, so Anita Brookner we’ve talked about seeing through things, through romantic myths. Exactly the kind of romantic myths in fact that go into Edith’s books. And Edith sees through them too, but she just gives the people what they want.

And just before she goes off to Hotel du Lac, she has lunch with her agent and this is what she says, “And what is the most potent myth of all? The Tortoise and the Hare. People love that one, especially women. Now you will notice, Harold,” that’s her agent, “That in my books it is the mouse-like unassuming girl who gets the hero, while the scornful temptress with whom he’s had a stormy affair, retreats baffled from the fray never to return. The tortoise wins every time. This is a lie, of course.

“In real life, of course, it’s the hare who wins every time. Look around you. In any case, it is my contention that Aesop, who wrote the fable about the hare and the tortoise, was writing for the tortoise market. And then you could argue that the hare might be affected by the tortoise lobby’s propaganda. Might become more prudent, circumspect, slower, in fact. The hare is always convinced of his own superiority. He simply does not recognise the tortoise as a worthy adversary. That is why the hare wins. In life, I mean. Never in fiction. At least not in mine. Facts of life are too terrible to go into my kind of fiction.”

But obviously they’re not too terrible to go into Anita Brookner’s kind of fiction where the hare wins every time. So should we have a look at maybe some of the characters in hare and tortoise terms?

Jo Hamya:

Yes. I think one slightly important thing to pick up is the provocation that gives rise to this running monologue by Edith. Which is Harold again, agent, says to her about this new book that she’s writing, “I like the idea of the new one, although I have to tell you that the romantic market is beginning to change. It’s sex for the young woman executive now. The Cosmopolitan reader, the girl with the executive briefcase.”

And he says, “She wants something to flatter her ego when she’s spending a lonely night in a hotel, she wants something to reflect her lifestyle.” To which Edith quite acerbically says, “Harold, I simply do not know anyone who has a lifestyle.”

James Walton:

I absolutely go with that. What happened to the word life? I mean, lifestyle? Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

So who are the hares and who are the tortoises? Edith, I suppose, would definitely see herself as a tortoise. A person who gets thought of last. Although I wonder to what degree this is self-inflicted. Something that Edith is very prone to doing in the novel is constructing these elaborate fantasies about whatever situation she’s in, which turn out to be completely untrue or they never really pan out.

When she first meets Mrs. Pusey and her daughter, Jennifer, for example, she imagines them to be 20 years younger than they actually end up being. She imagines a great wellspring of love and affection between them. In fact, that’s not true. Jennifer is a much more complex character, not quite as virginal as Edith paints her in her head.

And I wonder to what extent her tortoise-like nature is the result of this habit of withdrawing into herself in order to construct fantasies that are better than the life she’s living. I mean, even these letters that she writes to David continuously throughout the novel, essentially narrating the events of what’s going on in the hotel, actually serve to estrange her from building any proper connections with its occupants.

James Walton:

Well, she is a writer. I suppose, so that’s-

Jo Hamya:

Well, I’m a writer and I think I don’t do that. There’s a point in the middle of the book where Mr. Neville says to Edith, “You do not need more love, you need less. Love has not done you much good, Edith. Love has made you secretive, self-effacing perhaps, dishonest.” And Edith takes this very badly and she walks off from Mr. Neville’s point.

And it goes, “To contain her anger, for she could not find her way down to the lake unaided, she tried various distancing procedures, familiar to her from long use. The most productive was to convert the incident into a scene in one of her novels. ‘The evening came on stealthily,’ she muttered to herself. ‘the sun, a glowing ball.’” And this is something that she frequently does.

I think it does make her quite a tortoise in life. If she were to engage properly, perhaps she might become more hare-like if she were to simply get out her own head.

James Walton:

I think that’s what Mr. Neville offers the choice to whether she’s going to go hare.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah.

James Walton:

But she talks about the fear she always felt in the presence of strong personalities. Edith, once again anonymous and accepting her anonymity, whereas Mrs. Pusey, Iris Pusey and Jennifer are just… Well, first time she meets them, they rather patronisingly invite her over for coffee. But she has sad eyes. Is that right?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah.

James Walton:

Which reflects the following day. She says, “Iris held the stage. Iris, it was clear, was the star. Like many a star who could only function from a position of dominance. She held information at bay that Edith was not required to give an account of herself.

“Her and her daughter basking in the high summer of their self-esteem, which in its turn, shed a kindly light on those within its orbit.” So she completely sees through Iris. One bit where she… Again, this is the bit where I think you wondered how much there is compassion.

Jo Hamya:

Yes.

James Walton:

So Mrs. Pusey presented her with an opportunity to examine and to enjoy contact with an alien species. Being this charming woman so entirely estimable in her happy desire to capture hearts. So completely preoccupied with the femininity, which has always provided her with life’s chief delights, Edith perceived avidity, grossness, ardour.

But at the same time, she slightly envies her, slightly wishes she could be like her. At one point she writes to David and says, “I adore Mrs. Pusey.” And she’s not quite lying, is she?

Jo Hamya:

I don’t know. She changes her mind fairly quickly. But it is quite a short novel. The character I find intensely interesting who I wanted to hear more and more out of in this book, was actually Monica, who I think initially Edith imagines to be a tortoise as well. But I think breaks down the idea of that false binary ultimately is tortoise-like and hare-like. When Edith first observes her at a distance, she thinks of Monica as the tall, mysterious woman with a dog who probably never really speaks to anyone, who’s never really engaged in what’s going on in the hotel. A bit like Edith.

When they do finally speak, Monica’s lighting a cigarette and they get to talking. All of a sudden she starts coming out with all these details about the hotels occupants, which is actually the only way that we learn objective facts about them. She talks about Madame Bonneuil’s son. Monica says, “Poor old trout. She lives for that son. She’d do anything for him. And he comes to see her once a month, takes her out in the car, brings her back and forgets her.” And Edith goes, “How do you know all of this?” Then Monica says, “Well, she told me.”

James Walton:

Yeah, true.

Jo Hamya:

And it’s, I think, quite interesting. I think Monica is an example of a truly complex woman in the book. Perhaps the only real example of a complex woman rather than an archetype in the book. She fascinates me a lot, and perhaps we can move on to talking about the idea of womanhood and portrayals of femininity, which is so central to it.

James Walton:

Yeah, well, I’m slightly nervously raise this, but Dorothy Parker, a great wit of the ’20s, her first ever published poem was called, I hate Women. They get on my Nerves. And there seems to be a touch of that in this. I mean, she in her pining for the company of men all the time, right from the beginning, women only, “And I so love the conversation of men.”

And then when a man shows up, Mr. Neville, it was agreeable to see men after days in this gynaeceum, bringing the place to life. When she talks to Monica, she says, “I wish my mother could have lived long enough to see I’m like her in the only way she valued. We both preferred men to women.” “Well, who doesn’t?” said Monica.

And even her friend Penelope, this is her big mate. She just at one point… But again, it’s mixed. So Penelope has lots of affairs and is a bit Mrs. Pusey-like in her enjoyment of her own charm and money and things. And it talks about her bed at one point, “Penelope’s own bed would’ve accompanied four adults and which, when not in use, was heaped with all manner of delicate little pillows covered in materials which proclaim to the world at large, ‘I’m a woman of exceptional femininity.’ Some women raise altars to themselves,” thought Edith then “and they are right to do so, although I doubt if I could ever carry it off.”

Jo Hamya:

But she can though. I think one of the funniest moments in the book is again, it’s well-established by Edith that she apparently looks like Virginia Woolf. And early on into her acquaintance with Mrs. Pusey, this exchange happens. “You know, dear,” said, Mrs. Pusey, after she had repaired her face and received compliments on her appearance, “you remind me of someone. Your face is very familiar. Now who can it be?.” “Virginia Woolf.” Offered Edith, as she always did on these occasions. Mrs. Pusey took no notice, “It’ll come to me in a minute,” she said, “you two girls talk amongst yourselves.”

And so Edith tries to talk with Jennifer. And then finally, at the door, Mrs. Pusey turned dramatically and said, “I’ve remembered. I’ve remembered who Edith reminds me of. Princess Anne,” cried Mrs. Pusey. “I knew it would come to me, Princess Anne.”

James Walton:

That’s the end of a chapter, isn’t it? So it’s a proper punchline, that.

Jo Hamya:

It is. And I think Edith does build monuments to herself. She’s just astoundingly hypocritical about the foibles that she accuses other people of. She is entirely suspect or rather susceptible to them herself. And this idea of, “I prefer the company of men.” I suppose now you would call it a girl’s girl, is the lingo. Perhaps this maybe if we want to go down a feminist route or a psychoanalytic route, this internalised misogyny or internalised self-hatred that she has of herself.

The things she finds contemptible in other people tend to be things that she shrinks back from in herself. So, the Pusey’s greed or avariciousness. Well, I mean, why is she at the hotel? It was because of a moment of pure selfishness and greed of jilting poor Geoffrey at the altar.

James Walton:

It never crossed my mind, I don’t think, really that Edith was as much of a self-mythologizer as all the people around her. Do you think we’re meant to notice that?

Jo Hamya:

I think so. I think Brookner makes a lot of jokes-

James Walton:

Do you think Brookner’s [inaudible 00:24:29] to that-

Jo Hamya:

… at her expense.

James Walton:

… as they say?

Jo Hamya:

Well, Brookner makes a lot of jokes at her expense, like the Princess Anne one that I just read out.

James Walton:

Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Jo Hamya:

And I don’t think we’re supposed to find her… There’s an interesting part in the interview that she did for the Booker ceremony where I think she calls Edith’s character naive and a bit stupid.

James Walton:

Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

And I did find Edith that. Like I say, Monica was the star attraction of the novel for me, even though she’s not necessarily the one propelling it.

James Walton:

And Mrs. Pusey was my favourite, just livens things up whenever she shows up.

Jo Hamya:

Well, we all want Mrs. Pusey’s lifestyle. Who doesn’t want their husband to give them massive amounts of money to go off to the south of France and buy Hermes scarfs?

James Walton:

“But darling, he simply adored me.” Okay, well, we both liked it, but will we like it more than we like J.G Ballard’s Empire of the Sun? Can you tell us a bit about himself, Jo.

Jo Hamya:

James Graham Ballard was born in Shanghai in 1930 to quite wealthy parents, I think his father was in textiles. And they lived in the Shanghai International Settlement, which is an enclave of wealthy English and American people, had quite a high-flying lifestyle, which comes into Empire of the Sun. Actually, a lot of this biography that I’m doing now is almost a summary of Empire of the Sun, as you’ll come to see.

James Walton:

You saved me quite bit on my plot summary here, Jo.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. After the events of Pearl Harbour, Ballard, his parents and his sister were interned in a Japanese prison camp. So at that point, Ballard was, I think, 11, and there until the age of 15. I think he wrote in the 1990s about the experience for The Sunday Times. And he describes an extremely strange, which again, crops up in the novel, set of circumstances where he talks about feeling quite estranged from his mother and father in the camp who quickly realised that they had no leverage or means of control over the children.

And so just sent them out to run… well, as much as you can run riot in an internment camp. Lived on a very paltry diet of sweet potatoes and congee and tomatoes that eventually his father started growing. They used to pick weevils out of the wheat in the congee and his father at some point decided that he needed the protein. And so he began eating the weevils, which is another detail that crops up in Empire of the Sun.

But Ballard writes in this quite striking way in that Sunday Times article about how after the events of V Day or VJ Day, the war did not end very quickly for the prisoners in that camp. And even those Englishmen who left to return to the district in Shanghai, where they had been living before, were brought back a day later by Japanese trucks exhausted, having been unable to finish their journey. And also no one was really sure whether the war had entered or not.

James Walton:

And also, which is in the book too, another war had begun, which was the Chinese Communists versus the Chinese, what the book refers to as the Puppet Regime that had been in place under the Japanese.

Jo Hamya:

Yes. Nevertheless, after the war, Ballard was sent to England. I was about to say sent back to England, but in fact up until that point he’d never been in England.

James Walton:

No. No.

Jo Hamya:

He was sent to boarding school. And I think he spoke at that length about finding England a very strange place to be after Shanghai. He describes Shanghai as a Asian Paris at the time that he was there, very gaudy and glitzy. And I suppose in terms of his existence, it was, as the son of a wealthy textile businessman.

James Walton:

That’s right. He couldn’t believe how tiny English cars were, things like that.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, found it very depressing.

James Walton:

Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

But nevertheless, after school, trained to be a doctor or a surgeon. He talks about dissecting cadavers being a very useful thing for a novelist to know how to do.

James Walton:

It didn’t go much further than the cutting up of the corpse, his bit of medical training, I don’t think. But he certainly did that.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, also very interesting because doctors frequently crop up in his novel. In Empire of the Sun, it’s Dr. Ransome and the main character in High-Rise… there’s a doctor as well. There’s this very protracted scene of him opening up a skull. But anyway, I digress. After his medical training, decided that perhaps medicine was not for him, went on to train as a Royal Air Force pilot.

And then pivoted again after a year to marketing and advertising, which somehow still was not quite a good fit. And then, finally, in the early to mid-’50s, began writing a string of incredibly influential and successful novels, which have been called science fiction, though Ballard himself disclaimed the use of the genre on his books.

He said that, “Most people who reads science fiction seriously do not consider my work to be science fiction. They consider me to be a virus that has infected the nucleus of the genre and completely destroyed it.” But there is, I guess, a general consensus on the idea of Ballardian novels.

James Walton:

Yeah, it’s in the dictionary actually.

Jo Hamya:

Yes. And Ballard’s novels tend to be described by stories which involve some form of dystopia or societal collapse. They involve bleak, manmade landscapes. And they play out the psychological effects of technological, social, and environmental developments. Part of that’s from dictionary.com.

James Walton:

Really? So that’s Ballardian for you.

Jo Hamya:

There you go.

James Walton:

[inaudible 00:30:15].

Jo Hamya:

And Empire of the Sun, curiously enough, is the only book that Ballard was ever shortlisted or indeed longlisted for the Booker Prize. But other titles include The Drowned World, The Burning World, The Crystal World-

James Walton:

Yeah, that was the world falling into bits in various ways.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. Concrete Island, Crash and High-Rise. So Ballard, for the most point, after all this excitement lived a fairly calm, orderly and bourgeois life in the London suburb of Shepperton. It was a rather sad detail about the fact that three kids into his marriage in 1964, his wife contracted pneumonia while on holiday in Spain and died just a few days later.

So effectively Ballard was a single father for most of his children’s life. I think the oldest at that point was nine years old, but he himself died in 2009. And towards the end of this episode, when we’re comparing Ballard and Brookner and the shock of Brookner’s win, I think we can talk a little bit more about what an influential person he was to the ’70s and ’80s culture.

James Walton:

It’s interesting. Shall I give a bit on Empire of the Sun?

Jo Hamya:

Yes.

James Walton:

Some of this is covered in the biography bit that you’ve just done because the main character is a boy called Jim, who’s 11, was born in Shanghai in 1930. Businessman, father. He’s 11 when the book begins in 1941, the day before Pearl Harbour and living in some colonial splendour completely isolated from the local people, apart from servants and chauffeurs. Takes great interest in planes.

But then unlike the young Ballard, Jim sees the moment where the Japanese warship sinks a British ship in Shanghai Harbour and the invasion begins. So Japanese were already in Shanghai, but the International Settlement had been left alone and after Pearl Harbour it was invaded too.

And this is the big difference from the book and his life is that, as you said in life, he was interned in the camp with his parents and his sister. But in the book he gets separated from his parents, there is no sister. And for a while lives alone in the city, in his old house on his own, then some neighbouring houses.

He’s got two dodgy American merchant seamen called Frank and Basie hiding out in a truck. I know they take him in, that might be because they want to sell him to the Chinese in some way. Eventually he manages to get himself captured by the Japanese, which he’d been trying to do for a while.

He’s taken to a detention centre and from there after a long and terrible journey with badly sick detainees, Lunghua Camp. Ballard is what you said about the idea he felt estranged from his parents inside the camp. So that change of him just being on his own in the camp without his parents in the book, he felt was truer to his actual experience.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, there’s an interesting point at which he’s being interviewed when he says, “When I came to write Empire of the Sun, I thought I would have to follow my own life and have the parents in the camp too. But it didn’t really give the right impression. People would think that if the parents were in the camp as well, then they would be able to protect Jim and that he wouldn’t be in any danger. And that they’d never be in any danger from the Japanese or that he would never be in any danger for himself or his own growing imagination. I felt that this just wasn’t true, and so I decided to make him a war orphan.”

James Walton:

Interesting. So he arrives at the camp more or less halfway through the book, and then we cut to more or less the end of the war when the Japanese are losing, and the camp is now being regularly bombed by the Americans. I mean, one of the big and interesting ideas in the book is that basically that Jim enjoys the war, enjoys his time in the camp.

He’s running errands for Basie, this is a dodgy American who’s turned up there too. Prisoner then marched out to the camp by the guards back to Shanghai. Whereas, you said there’s some confusion for a while about whether the war has in fact ended or, and if so, whether a new one has begun because the Chinese Communists are now invading Shanghai. And of course they would win in 1949.

But I read this book at the time and I thought if you’d asked me before I reread it for this, what it was about, it’s about his time in the prison camp. In fact, it’s in the prison camp for less than a quarter of the book there.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah.

James Walton:

Which came as a surprise to me. But anyway, he has acknowledged that it is autobiographical, and that the character of Jim is true to the boy he was. So what do we make of Jim? He does carry the book really, doesn’t he?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, he does. I think a lot of the novel’s weirdness is down to the narrative perspective that we get from Jim. Who, at the beginning of the book is 10 or 11 and by the end he’s 14, 15 ish, so like Ballard himself. But is, I guess partly due to his extremely wealthy and colonial upbringing and partly due to the fact that he has ended up in circumstances which his life has just utterly not prepared him for.

Going from upper class apartment to internment camp, has this very strange distance to cruelty, this very weird ability to adapt and accept these quite horrific scenes that are printed upon him without really suffering too much psychologically. I mean, when you describe this book, you think, “Oh my God, well this poor young boy, he must be entirely broken by the end of the novel.” And in fact, he’s incredibly cheerful. He is actually quite sad that the war has ended.

James Walton:

Yeah, and in fact, we’ve got a clip here of Ballard admitting that he enjoyed the war talking I think on BBC 4’s Bookclub programme.

J.G. Ballard:

The curious thing is that despite what readers of Empire of the Sun may think, really, if I’m honest, I enjoyed the war. I had a wonderful time. I mean, even though I was probably ill much of the time because about half the people in the camp suffered from malaria. Despite all that, I was happy. I mean, I was with this enormous nuclear family and I was a teenage boy running wild. Wonderful.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. And I think this is where a lot of the strangeness of the book comes from. I mean, other than the fact that it’s a war novel and war novels are always quite strange. But that, in the first place, Jim is quite immune in a class sense to a lot of the poverty around him in Shanghai. So, there’s a point about five pages into the book where he’s in a very luxurious Packard car, which a beggar boy runs past.

And there’s a passage that goes, “Seizing his chance, a barefoot beggar boy ran beside the Packard, he drummed his fists on the doors and held his palm out to Jim shouting the street cry of all of Shanghai, ‘No mama, no papa, no whiskey soda.’ Yang who was the chauffeur lashed at him, and the boy fell to the ground, picked himself up between the front vehicles of an oncoming Chrysler and ran beside it. ‘No mama, no papa.’ Jim hated the riding crop, but he was glad of the Packard’s horn. At least it drowned the roar of the eight gun fighters, the whale of air raid sirens in London and Warsaw.”

James Walton:

Yeah, no, it’s absolutely got the colonial heartlessness. When the book came out, there was quite a lot of shock, and I think among hardcore Ballardians disappointed that he’d written such a conventional novel really about his own life and his own experience rather than things like Crash.

But he said, and I think it seems to be right to me, that actually all these books had really been about his Shanghai experiences, all those destroyed worlds, all that weirdness, all those dystopias were just in a way versions of Shanghai.

And there’s bits in Empire of the Sun, which are straight realism, but could easily come from a science fiction dystopia. I mean, this early on, “An open truck packed with professional executionists swerved in front of them on its way to the public stranglings in the old city outside the tram station, the hundreds of passengers were briefly silenced as they watched a public beheading.” Even this, I mean this quite seems quite scientific to me. This is Shanghai and in its glory days.

Jo Hamya:

I didn’t know.

James Walton:

The biggest cinema in the world, apparently. “As they stepped from their limousines, the women steered their long skirts through the honour guard of 50 hunchbacks in mediaeval uniforms.”

Jo Hamya:

You make quite a good point about… I mean, because it’s a bit of a-

James Walton:

Oh, thanks dear.

Jo Hamya:

Well, on a different school. About the fact that, because I suppose the horrors in this book start quite early and only ever pile on more and more, whether they’re on a intimate scope relating to what we’re seeing through Jim’s eyes or historical one. We see the atom bomb go off towards the end of the war in 1945.

Did you ever begin to get numbed out because there’s this really interesting exchange, again, still quite early on in the book that I felt really encapsulated this slight numbness. Jim has been at this point separated from his parents and he’s probably looking for someone to start taking care of him because he’d been surviving on tinned goods in the apartment and getting quite bored.

So he goes to a shell company caretaker, a Russian man called Mr. Gurevich cycles over on his bicycle and he says, “Hello, Mr. Gurevich, I’m looking for my mother and father.” And he says, “But how could they be here?” The old Russian pointed to Jim’s bruised face and shook his head, “The whole world is at war and you are still riding your bicycle around.” This weird sense of pervading normalcy that Jim provides-

James Walton:

Jim tries to hold up. Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

… to weird… to surreal circumstances. After a while, I found myself almost floating through. It was quite a horrific plot.

James Walton:

On the numbing thing. No, I think that’s right. When you first sort of dead bodies in the streets, which apparently again has just happened, people couldn’t afford to bury the dead. If you fell down in the street, you’d just died. People would throw their children into the river when they died and they’d be bobbing up on the way the Yangtze River as happens in the book.

When you first read that, when you read that in the early part sections of the book, you’re riveted with horror. And then the more the book goes on, the more you’re not, in a way, but there’s quite towards the end, there’s any number of corpses with flies buzzing around them in there.

Jo Hamya:

Oh my God, there’s that really sad point where Jim ends up in the internment camp. He finds a friend of his parents called Mr. Maxted who doesn’t make it in the end. But shortly before he dies, Jim keeps scooping flies from out between his gums. And even at that point, I’m saying this now, it is some sort of huge emotional scene, but while I was reading it, I was like, “Oh yeah, Jim’s scraping flies out of Mr. Maxted’s gums.”

James Walton:

I think that’s exactly how the book… what’s one of the many brilliant things about the book really is, that desensitisation is… we feel it too. And that brings home the desensitisation that happens to people in war and that happens to Jim.

Jo Hamya:

Well-

James Walton:

But at first, well it has you riveted with horror. After a while you think, “Oh, there’s another corpse surrounded by flies.” And I think that’s quite a realistic, immersive almost way of making you… Immersive is a bit overused, I know, but you know what I mean? It makes you feel what war makes people feel, which is less and less as it goes on.

Jo Hamya:

I would suggest two counterpoints to that, just to make it interesting. One is that I think Jim finds something of a foil in Dr. Ransome a notes midway through the book, “He had formed his only close bond in Lunghua with Dr. Ransome, though he knew that in many ways the physician disapproved of him, he resented Jim for revealing an obvious truth about the war, that people were only too able to adapt for. At times, he even suspected that Jim enjoyed Latin for the wrong reasons.”

This is another very weird detail about the book, is that even when he’s in an internment camp, Jim has Latin homework and he’s there going, “[foreign language 00:42:06],” the whole time. “The brother of a games master at an English boarding school, one of those repressive institutions, so like Lunghua for which Jim was apparently destined. He had been working upcountry with Protestant missionaries…” And then it goes on.

But I think this covers the two things that I don’t think we’re meant to find quite normal about Jim. One is that he has a very strange capacity to adapt, and this is maybe because he is a teenage boy for most of this novel. And he has a kind of… I suppose that’s the point at which your imagination is really growing and he often… there’s a huge plot point throughout the book where he’s seeking out propaganda films from the Americans or the Japanese where he’s reading Life Magazine. He essentially wants any form of image or sound to feed his mind when he falls in with Basie, the American sailor.

He deludes himself in the idea that Basie likes having him around because Jim has been picking up a lot of new and interesting words like, luxurious or what have you. And then the other thing that I actually, it’s one of the few things that I managed to find continually strange or horrific about the book is this very weird colonial perspective that Jim has.

So when he’s growing with tomatoes and melons with Dr. Ransome in the prison camp, there’s this very odd moment where he goes, “He worked with the slow but measured rhythm of the Chinese peasants. He had watched as they realised their crops before the war.” And romanticises this idea-

James Walton:

The Chinese are very shadowy in this book. They really are. He admires the Japanese a lot, actually, including Kamikaze Pilots. He looks up to the Japanese at first, I think Ballard’s explained that when you’re a boy, you do tend to hear and worship winners. And at this point, the Japanese, the winners and the Chinese, the losers.

But there’s Chinese people outside the camp who are far more starving than the people inside the camp actually having to get some camp food. And Jim certainly regards them as he was delighted that they’ve got the Japanese to keep them out.

Jo Hamya:

To your point, there’s this bit, Jim’s meditating on the use of bravery and war. But he expresses some very interesting opinions in that process, “And talk of bravery, embarrassed Jim. War had nothing to do with bravery. Two years earlier when he was younger, it seemed important to work out who were the bravest soldiers, part of his attempt to digest the disruptions of his life. Certainly the Japanese came top, the Chinese bottom with the British wavering in-between.

“But Jim thought of the American aircraft that had swept the sky. However brave, there was nothing the Japanese could do to stop these beautiful and effortless machines.” I don’t know, maybe this is a function of childishness as well, and also of, at a very young age, having been put in the kind of extreme circumstances that mean morality, kindness, and so on don’t count for much. And-

James Walton:

Okay. He realises that at one point, I think that kindness is just… At one point he has that revelation, “He knew now that kindness, which his parents and teachers had always urged upon him, accounted for nothing.”

Jo Hamya:

No. He thinks about good behaviour or good actions as something that he can trade for future favours. There’s a point where we realise that he clearly has no scruples about stealing from the dead, has no scruples about even his own ill-treatment.

He shares a room with a family who go by the name of Vincent, and Mrs. Vincent, who’s terrible to him. At one point he’s got, I think it’s malaria, and he keeps trying to persuade her to take care of him. He says, “My parents will give you a reward.” And Mrs. Vincent just does not care. But still, he says that he feels a sense of weird attraction and an admiration for her.

James Walton:

I think because he fancies her essentially. So we have a 15-year-old boy, she’s by account prison camp internee standards.

Jo Hamya:

I suppose. Yeah, I’ve never been a teenage boy so…

James Walton:

I think all of that is part of… Again, one thing he said, “Looking back on it, one of the things I took from my wartime experiences was that reality was a stage set, a comfortable day-to-day life, school, the home where one lives, all the rest of it could be dismantled overnight.”

And I think again, that’s there in his, want of a better word, science fiction books as well, that everything is far more provisional than it appears. The world is far less settled than it appears, which is something obviously he’s got from having that weird experience of growing at Shanghai at that time. We need to move on to the big question then.

Jo Hamya:

Yes.

James Walton:

Oh, can I just do my really old journalist hacky thing. But one thing I really like about this, we talked about the theme of The Hare and The Tortoise, in Anita book, and how the tortoise never wins is crucial to her. And yet in this Booker Prize, she is definitely the tortoise and she wallops the hare of J.G Ballard. What a pleasing irony that is.

Jo Hamya:

Well, how much does she really? Because I’ve got the set of rather horrible little archival-

James Walton:

You’ve been looking into some of the reaction at the time-

Jo Hamya:

Yes.

James Walton:

… which was not favourable, was it?

Jo Hamya:

Malcolm Bradbury called Hotel du Lac, parochial. The New Statesman said it was pretentious, although it did caveat that by saying, “It’s not Brookner’s fault that she won the prize.”

James Walton:

No, that’s right.

Jo Hamya:

Which is just unbelievable. The Guardian was lukewarm in its assessment the following day, at best manages to compliment it by simply quoting other people who have already complimented it. And I don’t know. I mean, is it really a win when the next day you have to, as Brookner did, apologise for winning?

James Walton:

Well, she won. Let’s stick with that. No, I take your point. I think one of the problems, I’m still sticking with my hare and tortoise analogy, and here we have a clear tortoise victory. I think one of the things is the reason for that outrage, and I think particularly from, let’s face it blokes, was that Ballard was really cool at the time and not just in literary circles.

His early books had a massive influence on British electronic music in the late ’70s and early ’80s. So Joy Division song, Atrocity Exhibition named after one of his books. I didn’t know this, I didn’t know that, but I looked into it, Video Killed the Radio Star by The Buggles is inspired by one of his short stories according to the authors of it, according to the writers of the book.

Gary Numan’s Cars influenced by his work more generally, “Here in my car, I feel safest of all.” And there’s a early Human League track called 4JG. And the song Warm Leatherette by the Normal, which is based on Crash and was covered by Grace Jones. [inaudible 00:48:48] hence the lyrics, “The handbrake penetrates your thigh. A tear of petrol is in your eye. Quick, let’s make love before we die.”

Jo Hamya:

Oh, Christ.

James Walton:

So I think we feel we’re putting it off, we’re chickening out of our main job here, which is to say, “What do we think should have won out of J.G Ballard and Anita Brookner for the 1984 Booker Prize?” I’m going to go first.

Jo Hamya:

I suppose, I would say that for me it’s probably Hotel du Lac actually at the end. I think we talked previously about this idea of narrowness in it, and I thought a lot about that.

James Walton:

This is it too narrow. That was the thing, is it too small a book?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, I suppose what you might call its narrowness is down to the fact that it’s a perfectly circular and perfectly patterned novel. Every character has a foil, every storyline has this very neat conclusion that almost takes things back to the start. And in a way, after I’d finished it, I thought of it as a kind of fable that you’d give to women in their 20s and 30s in the same way that you use stories like Hansel and Gretel or Little Red Riding Hood, or the Boy Who cried Wolf to teach children something about the life that’s going to unfold ahead of them. I would maybe give Hotel du Lac to my girlfriends.

The other thing I think, is that in a way, it is a novel that is firmly of its time, and I think if I had read it on publication, I would’ve maybe found it a lot more striking, this question of… I mean, there is so much… The question of feminism in the book is something that I take so much for granted being 27 in the year of our Lord, 2004. This idea of choice in life or the extent to which one relies on, or one, I say a woman relies on marriage or love in order to have a suitable, acceptable life.

This idea of Edith being cast out of her own society because she has chosen not to take a boring husband is actually, I suppose, quite revolutionary for a novel that was published when marital rape was still legal. So, maybe my blunted response to Hotel du Lac is because I have so much freedom as a woman these days. Perhaps if I’d read it 40 years ago, I would’ve been so invigorated by it.

James Walton:

Okay, so you see your choice as for Hotel du Lac?

Jo Hamya:

Yes. I will say, just as a final point, I mean I liked these books well enough, but I wasn’t totally blown away by them as I have been with other Booker novels. But out of the two, I found it a little bit more difficult to get on with the Ballard. I thought it was a bit, I mean, necessarily disjointed because the flow of time in a war, as we’ve said with Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song-

James Walton:

That’s right. It was last year’s winner. Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

… which was last year’s winner, is often very strangely mapped out in a novel for obvious reasons. But also, I suppose I just… I felt that I skated on top of the novel. I never really managed to go into it. And so by that token Hotel du Lac wins for me. What about you?

James Walton:

Yeah, I mean, I’m very aware of that idea that a big boys book should be better than a slight similar book. And every time I read or rethought about or pondered Hotel du Lac I thought, “That’s an absolutely worthy winner. That’s a really good book.” But then when I turned to the Ballard, I thought, “No, this is more, this is better, this is stronger. There is more to it. This is the book that should have won.”

Jo Hamya:

Well, depressing is stereotypical here.

James Walton:

The bookies are right. Yeah, it is a shame, we’ve come down on stereotypical. I mean, I think going right back to that clip at the beginning where Melvyn Bragg said that was a real shock, but don’t forget Hotel du Lac’s a really good book. It actually was a summary that I put myself completely alongside.

Jo Hamya:

Oh gosh, I think I’d-

James Walton:

And Hotel du Lac, it’s not-

Jo Hamya:

… cry myself to sleep, how utterly depressing. It’s just the most backhanded way to win. It’s like saying, “Here you go, Anita, you’ve won.” And then just spitting on the award as you hand it to her, isn’t it?

James Walton:

I don’t think so. No, I think that’s harsh. It’s not a scandal that she won. I mean, we probably won’t get round to talk about books that we thought as an unbelievable scandal. It’s not. It’s a really worthy winner. But really-

Jo Hamya:

I think we’re allowed to talk about books that we think are scandalous winners.

James Walton:

But if we are, Hotel du Lac is not one of them, a perfectly worthy winner. But for me, Empire of the Sun in the end should have won really, the bookies were right and the Booker wasn’t. So score one all, I think. And let’s leave it down.

Jo Hamya:

Where does that leave us? What did we agree last time with Arthur and George?

James Walton:

I think last time we did this with Arthur & George versus The Sea by John Banville.

Jo Hamya:

Oh, you wanted the Banville and I wanted Barnes.

James Walton:

Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

Yes. And I’ve gone for the winner both times. How conventional of me.

James Walton:

Oh yeah, I’ve been the rebel outsider. The Desperado.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, I know. Even as I’m here trumpeting my feminist values, actually I’m just giving into the man.

James Walton:

Yeah, a bit of a corporate shill. Anyway, that’s-

Jo Hamya:

On that note.

James Walton:

On that note, Jo’s corporate shill, me as reckless outlaw. We will end the Booker versus the bookies for this episode. So that’s it for another week, Jo. You can follow The Booker Prizes at thebookerprizes.com. There’s also Facebook isn’t there? Where you can join the book group, that’s for sure, TikTok, Twitter and Instagram.

And even more importantly, don’t forget to rate and review this podcast wherever you get your podcast. That really does help if you follow us and you rate us and review us, and thanks very much for listening. Until next time, goodbye.

Jo Hamya:

Goodbye. The Booker Prize Podcast is hosted by me, Jo Hamya and by James Walton. It’s produced and edited by Kevin Muyolo, and the executive producer is John Davenport. It is a Daddy’s SuperYacht Production for The Booker Prizes.