Small Things Like These

by Claire Keegan

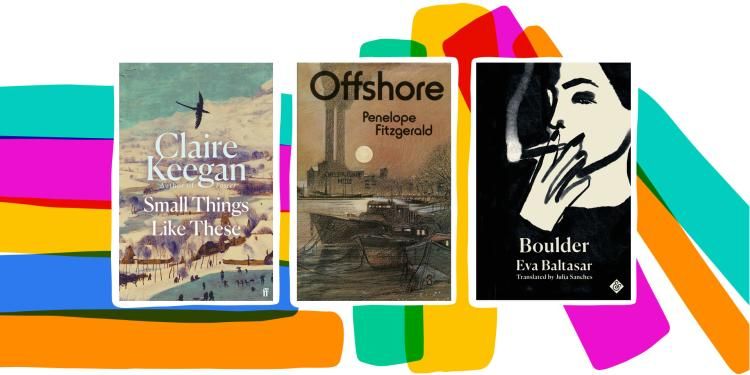

On The Booker Prize Podcast this week, Jo and James recommend the best compact novels from the Booker Library, perfect for those moments when there’s nothing else to do but curl up with a good book

Listen to more episodes from The Booker Prize Podcast here.

Embed code:

It’s winter in the northern hemisphere right now and we are simply filled with the urge to hibernate. If you’re feeling the same vibe and want to stay in with a good book, allow us to recommend three short books that could keep you company through a weekend. Listen in this week to hear Jo and James discuss some of the most bijou of novels from the Booker Prize and International Booker Prize archive.

Jo Hamya and James Walton

© Hugo GlendinningTranscripts of The Booker Prize Podcast are generated using both speech recognition software and human transcribers, and as a result, may contain errors.

—

Jo Hamya:

Hello and welcome to the Booker Prize Podcast with me, Jo Hamya.

James Walton:

And me, James Walton. And today, we’re kindly supplying what we hope will be a useful Booker hack. If one of your New Year’s resolutions was to catch up on a spotted Booker related reading, and why wouldn’t it be? Here’s how to knock off three, count them, three Booker novels easily in a single weekend and still have plenty of time to go on a 50-mile bike ride, or watch a lengthy box set with some wine, whichever you prefer. Because what we’re doing today is taking a look at three of the very shortest Booker novels that they’ve ever been but before we do that, Jo, what about your New Year’s resolutions? And a couple of weeks into the new year, how are they going?

Jo Hamya:

Oh. My one resolution for this year is to chill out. I’ve made this resolution that unless the world is actually literally ending before my eyes or if someone is dying, someone close to me obviously, I will not be stressed, anxious, worried, et cetera. I think it’s going really well. I spent the first week of the year sleeping, and the report for this week is that I haven’t been stressed.

James Walton:

Cool. So you’re on coasters.

Jo Hamya:

I am. And who knows? Maybe in a few episodes’ time, you’ll begin to hear cracks in my voice.

James Walton:

Let’s see if we can get through this episode all in that calm unstressed manner.

Jo Hamya:

Don’t piss me off, James.

James Walton:

I’ll try not to. I went for the usual one of going on a diet, which was going all right, apart from the bacon sandwich I just had before we did this recording.

Jo Hamya:

That’s fine though because I had an English breakfast, so next to me, you’re really saintly.

James Walton:

No, no, that did make me feel better. Obviously, I’ve also had to load up on fags because if you don’t give up smoking for the new year, all the people who do in the first few days of January just come over and say, “Do you mind if I have a cigarette?” So you do have to have loads.

Jo Hamya:

Do you find that…? I used to find that really annoying when I smoked actual cigarettes, but I rolled them, so I had to go through the whole process of actually rolling someone a cigarette.

James Walton:

I know this way, and this way.

Jo Hamya:

You just hand them out.

James Walton:

You just hand them out.

Jo Hamya:

Man of pleasure.

James Walton:

Of course, when people give up smoking, it’s always like you feel a bit abandoned. So when they’ve failed after three days, you think, “Oh, well, welcome back.

Jo Hamya:

I’m not sorry.

James Walton:

“Welcome back my friend.”

Jo Hamya:

I do think about the fact that our initial bonding point was just smoking.

James Walton:

Yeah, it was.

Jo Hamya:

And now I’ve left that, but happily we have firmer ground.

James Walton:

You’ve abandoned me.

Jo Hamya:

It’s okay, but we’re still together.

James Walton:

We are. We are.

Jo Hamya:

We’re going strong.

James Walton:

And I must say looking forward to this episode. As I say, Booker hack, how can you read three Booker novels in a weekend, plenty of time?

Jo Hamya:

Well, just out of sheer curiosity, how long did it take you? Did you read them all at once?

James Walton:

I mean, they were short. I suppose it is different when you’re making notes and thinking about what you might say in a podcast.

Jo Hamya:

That’s true.

James Walton:

But I think for people listening who just want to read it, that these will hurtle by. They’re not unsubstantial, so there’s something to them. [inaudible 00:03:16] I read them at 100 pages an hour particularly, but most of them are around 100 pages, so a couple of hours should get you through all of each of them, I think.

Jo Hamya:

I did two in one day and then did another one day after. So shall I start-

James Walton:

Yeah, why don’t you kick us off?

Jo Hamya:

… with our first book?

James Walton:

I believe you’re kicking us off with the shortest ever shortlisted book.

Jo Hamya:

Is it?

James Walton:

Yeah, apparently, according to the Booker website anyway.

Jo Hamya:

Oh, okay. Well, trust them. It’s Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These. It was shortlisted in 2022, along with another extremely short book, Alan Garner’s Treacle Walker and also Elizabeth Strout’s Oh William! Percival Everett’s The Trees, NoViolet Bulawayo’s Glory, and that year’s winner, Shehan Karunatilaka’s The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. And you can listen to our interview with Shehan-

James Walton:

Yeah, friend of the show.

Jo Hamya:

… on this podcast as well.

James Walton:

Just before Christmas I believe.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. So my copy is 110 pages - very slim.

James Walton:

With quite a lot of white space.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. It’s a small novel, but it’s got a huge moral and political underbelly. So in 1985, in the weeks leading up to Christmas in a small Irish town, a coal merchant named Bill Furlong is working his busiest season. Bill does well for himself, but the threat of poverty is never far off. There’s Thatchers Britain looming in the background and we’re made constantly aware of rising rates of unemployment in the town where Bill lives.

Still, we learn about his family, his wife, Eileen, and his five quote “flourishing” unquote daughters for whom he feels extremely grateful. And we also learn that this gratitude stems in part from his own upbringing because Bill’s mother was an unmarried woman when she had him. There’s no higher sin in Catholic Ireland at the time.

James Walton:

And then 16 as well, wasn’t she?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. But she was fortunate enough to be taken in by her Protestant employer, Mrs. Wilson, and kept in reasonable comfort until her very sudden death.

One day Bill makes a delivery to the local convent and discovers, locked in the coal shed and surrounded by her own excrement, a young girl called Sarah, and Sarah asks after her baby. We’re just going to hear Sharon Horgan reading a short extract from that moment.

Sharon Horgan:

“When he let down the tail board and went to open the coal house door, the bolt was stiff with frost, and he had to ask himself if he had not turned into a man consigned to doorways, for did he not spend the best part of his life standing outside one or another, waiting for them to be opened. As soon as he forced this bolt, he sensed something within but many a dog he’d found in a coal shed with no decent place to lie. He couldn’t properly see and was obliged to go back to the lorry, for the torch. When he shone it on what was there, he judged by what was on the floor, that the girl within had been there for longer than the night.

‘Christ,’ he said.

The only thing he thought to do was to take his coat off. And when he did, he went to put it around her.

‘There’s no harm,’ Furlong explained. ‘I’ve just come with the coal [inaudible 00:06:30]. God love you child,’ he said. ‘Come away out of this.’

When he managed to get her out and saw what was before him, a girl just about fit to stand with her hair roughly cut, the ordinary part of him wished he’d never come near the place.

‘You’re all right,’ he said. ‘Lean in on me, won’t you?’

The girl didn’t seem to want him close, but he managed to get her as far as the lorry where she lent against the warmth of the bonnet, and looked down at the lights of the town, and the river and then far away out, much as he had done, at the sky.

‘I’m out now,’ she managed to say after a while.”

Jo Hamya:

And that was recorded for the 2022 Booker Prize ceremony. And you can find that clip and many others like it on the Booker Prize’s website.

So the convent, as it turns out, is a Magdalene laundry. Now, for those who don’t know, Magdalene Laundries operated in Ireland from the 18th century until as recently as 1996. They existed ostensibly to house fallen women, i.e., unmarried mothers and their babies, but the word “house” is a really poor choice of verb. When one considers that these women were brutalised, worked to the bone for no pay, or really for any of the civil dignities afforded a citizen really. Their children often died and the women who didn’t survive were hidden in unmarked graves.

James Walton:

If the children did survive, they’re often just taken away from them and given to couples in America and Australia, and so forth.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. So Bill returns home with this new knowledge of Sarah’s existence and the conditions of her life and is left really to the machinations of his conscience. Should he do something to help and therefore honour the moral foundation upon which his own existence was made possible (his mother being taken in by Mrs. Wilson), but in so doing risk, the economic and political safety of his family in a deeply Catholic country, a country where the church is bound up with the state? Or should he pretend, as his wife really wants him to, that he never saw a thing in the interests of keeping his family fed warm and welcome in their community?

James Walton:

And also educated because these same nuns operate the only good school for girls in the area, so all the girls have already gone there. He wants his younger girls to go there to have a chance in life, but if he alienates the nuns, who knows what will happen to them and to his business? That’s right, isn’t it?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah. Just a note about Claire Keegan herself: it’s the first time with this book that she’s been shortlisted or even I think long-listed for the prize. Her other books are collections of short stories. They include recently published So Late In The Day and Foster. I think they are both less than 100 pages, those other two, so she is versed in this extremely short form.

She was born in 1968 in County Wicklow. She had a brief stint in America as a young woman for uni, then Wales, then back to Ireland for a PhD. And to my knowledge, at the moment, she still teaches private creative writing classes and she’s also what my generation would call a horse girl. She tames and rears wild horses.

James Walton:

I didn’t know that.

Jo Hamya:

She says she keeps them very simply, just eating hay in a field. But I genuinely really think that Small Things Like These is like a miniature masterpiece. I think it’s probably going to be one of my favourite books from this year, if that’s not too soon to say in January. What did you think of it, James?

James Walton:

I thought it was fantastic too. There’s plenty to discuss. In a way, I wasn’t sure if it was the angriest calm book I’ve ever read or the calmest angry book I’ve ever read.

Jo Hamya:

Oh, that’s interesting.

James Walton:

The conditions in the laundry, which have since become quite familiar, but in 1985 was still largely unknown. Or were they? That’s the question is, did the townspeople sort of know what was going on and deliberately turn a blind eye? But it wasn’t until the late 90s that all of this was exposed and has since become a series of films as the one that Steve Coogan won, isn’t it - Philomena? It’s about that, isn’t it?

Jo Hamya:

Really?

James Walton:

Yeah.

Jo Hamya:

Oh God, that makes me watch to watch it.

James Walton:

With Judy Dench.

Jo Hamya:

And then there was that BBC show, The Woman in the Wall.

James Walton:

The Woman in the Wall. There was a film called The Magdalene Girls. It’s now become a source of great scandal and played not a small part, I think, in the death of Catholic Ireland really in the end: the Catholic Church’s power over Ireland once this all came.

But she said about the book, which I think is interesting, which we can discuss, is that, “It’s quite easy to read it as a book about a quiet hero, Bill.” And she said, I think quite interesting, “It’s not quite so simple, the choice he faces. Would it actually be an act of self-destruction to rescue this girl? Would it be the product of what’s clearly a midlife crisis? If he was to rescue her, he would put his daughters at risk and he would put his business and therefore family at risk.” So he’s a bit more tormented than we think. Those are the two things I’d say as well is the precision of the Catholic references.

So this is 1985 where Catholic Church is still powerful in Ireland, but it’s beginning to come to an end. There’s just one word really, right at the beginning. He talked about, “The nights came on, the frosts took hold again, and the blades of cold slid under the doors and cut the knees off those who still knelt to say the rosary.” So, there are still people needing to say the rosary, but now you need the word “still” because they’re still going on. This is the workers in his coal and timber yard. “The Angelus Bell rang - that’s a call to prayer really. “When the Angelus bell rang at noon,” so still Catholic Ireland, “the men laid down their tools, washed the black off their hands, and went round to [inaudible 00:12:29] where they were fed hot dinners, and soup, and fish and chips on Friday.” So it’s still fish on Friday, but the Angelus is now a call to lunch, so there’s that beginning to break down.

The other thing in a book as short as this, I wondered for a while why there was such leisure descriptions of making the Christmas cake and writing to Santa, and just him going about his work when there’s all this… well, there’s this massive question in the background. I have developed a theory, which is it’s the influence of WH Auden’s moderately famous poem Musée des Beaux Arts which he wrote in after going into a Belgian art gallery about… It’s this, the one that starts off, “About suffering, they were never wrong, the old masters. How well they understood its human position, how it takes place while someone else is eating, or opening a window, or just walking dolly along.

So, while this huge suffering is going on in the background, people are just going about their business. And backing up my theory on that, is that that poem goes on to mention Brueghel’s poem Icarus where Icarus falls from the sky and nobody notices, life goes on. In fact, the cover is a Brueghel painting, not the same one, but I think that’ll do for my theory for that.

Jo Hamya:

Well, I feel like Claire Keegan has put this maybe slightly less poetically then you did James. But in a profile she did with Guardian, she said, “When I was young, my mother taught me that if I went to the butcher and was choosing a piece of beef to roast, it should be marbled with fat. And I actually see good prose in the same way: marbled with what doesn’t seem to be necessary.”

James Walton:

But it still gets in quite a lot of stuff about speaking, I suppose, autobiographically as you tend to do when thinking about books. It’s very good on fatherhood. There’s one bit where he talks about the deep private joy he has when he looks at his daughters and that they’re his, but also accompanied by anxiety, or what’s going to happen when they get out in the world.

Jo Hamya:

I, for many reasons, am not a father, but I thought the way I related to this book was… I mean, I’ve seen that some people describe it as historical fiction because it is so time-specific and context-dependent on the idea of the Magdalene Laundries. But I really saw a lot of the small moral decisions that we all have to make on a daily basis when reading the news taking place in this book.

Do you act on the terrible things that you know are happening around you, or do you just continue with your day? And I was really touched by this passage where Bill is having what Claire Keegan calls his midlife crisis. It goes, “ ‘Always, it was the same,’ Furlong thought. ‘Always they carried mechanically on without pause to the next job at hand. What would life be like?’ he wondered, ‘if they were given time to think and reflect over things. Might their lives be different or much the same or would they just lose the run of themselves?’”

James Walton:

That’s terrific. Also, I know it’s such a cliché to do the Second World War, particularly blokes of my age. It’s just like the Nazis, but I think that question of a people who… like the town knows what’s going on in the laundries or could know or might know, but chooses not to. And I think it’s quite interesting in a way that it’s Bill who’s the one who’s much agonised about this and his wife is far more practical. So when he says, “Look, I’ve seen this girl in this coal shed, what do I do?” And Eileen, his wife says, “If you want to get on, there’s things you have to ignore.”

Jo Hamya:

But I think this is really where the brilliance of this book lies because we’re making Eileen potentially sound a bit heartless, but I really didn’t see her as a villain at all, apart from the one dig that she makes at Bill because of his mother, but I never really saw her as a villain. Because when he tells her about finding Sarah in the coal shed, her concern is literally just for her children and you can’t fault her for that.

James Walton:

Well, can you, you see? I think that’s the question that this book holds up. But when she says, “If you want to get on, there’s things you have to ignore,” that might just be true. I mean, we all like to think that we’d all be heroic in all circumstances, but would we?

Jo Hamya:

No, we wouldn’t be. I think this is proven to us on a daily basis. I don’t know what news you read this morning, but there are certainly various marches that I didn’t go on this week, bits of news that I consciously avoided speaking about with my friends because it was the end of the working day and I just wanted to go to bed.

James Walton:

And you’ve got your news resolution as well.

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, and don’t stress unless the world is ending, which it might be. But anyway, my point is maybe Eileen seems much more sharp or pragmatic, but I think the scenes of her making the Christmas cake, ironing all of her family’s clothes, reading their letters, her children’s letters to Santa, and then deciding (like taking an hour at the end of the day to decide) what the best gifts she can reasonably get her daughters with the money they have is, I think all of those scenes serve to show you that she’s not just being heartless. She has a whole ecosystem within this house to keep afloat in the way that she says to Bill…

Bill worries that he doesn’t do enough for the house because she’s working so hard and she goes, “No, no, you’ve kept us afloat. You’ve kept your business afloat. That’s all we need from you. And then, what I do is to make sure that we are all fed, comfortable with the money that you provide.” Sure, you could read her as flinty, but I think the time that’s spent focusing on all the domestic labour she engages in really balances out this idea of her going, “Look the other way.” She has to, otherwise, what does she have?

James Walton:

I still think we are meant to admire Bill.

Jo Hamya:

Oh, without a doubt. Especially for honouring his mother’s legacy, is that the right word?

James Walton:

In the short book, there’s also quite a lot about his backstory and little plot twists on that as well. Well look, a book that we both agree is terrific and well worth the maximum two hours of your time - Claire Keegan, Small Things Like These.

So from the shortest ever shortlisted book to the shortest ever winner, this is Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore from 1979. It was also a surprise winner as apparently several newspaper headline writers had already decided that the prize that year would go to A Bend In The River by VS Naipaul, such a big gun that he later won the Nobel Prize in Literature. And in fact, according to one of the judges that year, Hillary Spurling, the reaction to Offshore’s victory was so shocked, he was amazed that it had won, that that reaction caused Fitzgerald quote “pain and humiliation ever after.”

And on a happier note, you could argue quite convincingly that her reputation is now higher than Naipaul’s who’s perhaps faded away in recent years while she’s now regularly acclaimed as one of the great novelists of the late 20th century mainly I think… well, particularly I think for her later historical novels, notably The Blue Flower published when she was 79, which won a National Books Critics Circle Award in the US whose previous winners have included [inaudible 00:20:23], Philip Roth, Anne Tyler, and Toni Morrison.

So who was she? I suppose you would want to know, Jo. She was born in 1916 to an intellectual family. Her father was Edmund, who later became editor of Punch, which was quite a thing to be in those days. Uncle Ronald became a Catholic convert and a priest, produced a very influential Catholic translation of the Bible. While his biography was written in 1959 by no less than Evelyn Waugh. It sounds as if Penelope was pretty clever too. She went to Somerville College Oxford where she got a congratulatory first and that’s where you do your exam, your tutors call you in and you think, “Oh, they’re going to interview me to see whether I should get a first or a second,” and when you go in through the door, they all stand up and applaud. So that’s what she got, a congratulatory first.

In the 1950s, she ran a literary magazine with her husband Desmond, who was a barrister, but who had come back from the war an alcoholic and was later done for forging signatures on checks, disbarred from the legal profession, and they fell on hard times. To help out, she taught at the Italia Conti stage school and the Queen’s Gate School where one of our pupils was the future Queen Camilla, very much a friend of the Booker Prize.

Her first book was 1975 when she was 59: a biography of the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones. Her first novel came in 1977 with The Golden Child. The second was The Bookshop, 1978, short-listed for the Booker Prize and then Offshore, which won in 1979. And those early works are all autobiographical, drawing on different aspects of that pretty varied early life.

Offshore itself draws on a pretty low point, which was when she was living on a barge on the Thames by Battersea Reach in the early 1960s, which is where and when the book takes place. The main character, if there is one, is Nenna, mother of two children: age 6 and 12. Her husband has left her mainly because he doesn’t want to live on a boat. Neighbours in this rather strange community include Maurice, who’s a male prostitute and her main confidante, Richard, who’s the boss there. He’d served in the Navy during the war, been torpedoed a few times, and seems as if he just couldn’t quite leave the sea or the water behind, so he’s there much to the dismay of his wife Laura who hates living on a boat. There’s an artist called Willis. There’s a few others as well, but they’re all basically adrift in their lives, metaphorically as well as literally.

What I like about this book is that Fitzgerald regards them all with a completely beady eye. They don’t get away with much. She knows what’s going on, but it’s also a kindly and amused eye, I think. Almost an epigraph for the book could be, “Lord, what fools these mortals be,” except that might sound like outright mockery, but she’s not mocking. It’s very sympathetic for all these rather lost souls, so I did like it an awful lot. Jo, what do you reckon?

Jo Hamya:

I liked it well enough. I think my only reservation is that it was such a large cast of characters. There are loads that you haven’t mentioned as well. Nenna’s daughters and the-

James Walton:

Who have interest in both in their different ways, aren’t they?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, and her sister in Canada and the cousin that comes to visit them. I think whilst all of them have really distinct personalities, foibles and amusing traits, I really enjoyed, there are I think, two passages where Nenna, as a way to go over the points of her separation with her husband, puts herself on trial in her head-

James Walton:

I love that bit.

Jo Hamya:

… and it makes for really fantastic back and forth between her conscience and her heart. It is actually as good as any marital disagreement you’ll read in any book, even though one party is absent, but I did sometimes feel like there was just too much happening in a book that was only 181 pages. It took me a while to… One of the motifs in this book is the fact that the boats that everyone lives on are all tied together. And so when one person’s misfortune occurs, it impacts the rest of the community, and whether it’s Willis who has to go live with other people or Maurice’s-

James Walton:

His Navy boat sinks. I don’t think that’s a massive spoiler. The rest of them react very kindly.

Jo Hamya:

Or Maurice’s sex work and the dodgy people he lets into his boat that comes back to bite poor Richard in the head actually quite badly. There are these echoes and reverberations across the entire plot. It’s very hard, as I say, in a book that’s this short and compact to keep a hold of everything. With a cast of characters this big or this large, you’d be looking at a book that’s at least 300 pages to get into the rhythm of knowing them all.

James Walton:

I suppose that’s what I really liked about it because I do think you get to know them all. Again, but I think it’s just as with Clarke Keegan, I suppose as with great small books, is just how concise she could be. Again, I think is a word that does a lot of heavy lifting, which is… Oh, this is Richard thinking about Laura, his wife. So this is Richard, the boss, sees Laura unhappy on the boat. “Laura’s problem was she had not had enough to do, no children, though she hadn’t said anything about this recently.”

Now that word “recently,” it means first of all, on the one hand, it means that she’s obviously said quite a lot about it in the past. On the other hand, it also means that she’s given up mentioning it now. So the entire arc of a marriage there in that one word “recently,” I think that’s brilliant, and things like that again and again. When we first see her, Laura is… Richard’s leading a meeting with the other boat people and she’s below deck… I’m not very good on me nautical terms… in the galley. Is that the kitchen?

Jo Hamya:

I have no idea.

James Walton:

[inaudible 00:26:35] what it is. Anyways, she’s doing that while he’s leading the people and he goes down to see how she’s doing, and this is the first time we have her. Laura was cutting something up into small pieces. So basically it doesn’t matter what she’s cutting up, she couldn’t care less. Time and again, I think that… I could give several more examples, but I’ll hold back for now, but that does allow her to give real depth to, as you say, a surprisingly large cast for such a short book, and I think enable you to keep them all. She gives them all an amazing ju.

There’s Martha, who is the older sister, the 12-year-old… sorry. So the 12-year-old daughter of Nenna who’s a bit like Saffy and Ab Fab. She’s the responsible one and she has to, in a way, look after her mother. And then, she has one great moment where her and this rather glamorous Austrian aristocratic kid who was about 16 or 17 shows up and she shows him around the King’s Road in Chelsea, which is quite close by. He’s slightly worried about it and he says, “I think you could be heading for a very serious depression,” and the reaction is “Martha felt flattered. It seemed to her she’d never been taken seriously before.” And again, just a world in that.

Jo Hamya:

Martha’s younger sister is Tilda and when they go out on the King’s Road, which I actually really love. I have this great affection for portrayals of a 60s London that I never lived in. But she says to her younger sister, Tilda, “I’ll give you anything you like within reason to go back to the boats and stay there.”

James Walton:

That’s right. She’s with a boy for the first time there, [inaudible 00:28:23]?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah, and it’s so sweet. You’re right. It is really good. That is a whole sisterly relationship in one sentence.

James Walton:

And she loves Tilda, “But just bugger off now. I’m with a boy.” So we’re told that these people are creatures neither of firm land nor water. There is a certain metaphor to them living where they live, so this is when we first meet them really. So they’re very near the Chelsea Shore where loads of people live with sensible occupations and adequate amounts of money, these people. “But a certain failure distressing to themselves to be like other people cause them to sink back with so much else that drifted or was washed up into the mud moorings of the great tideway.”

The idea of selling their boats, which some of they fantasise about moving back to dry land, “but to sell your craft, to leave the Reach,” that’s Battersea Reach, “was felt to be a desperate step like those of the amphibians when in the earliest stages of the world’s history they took ground. Many of these species perished in the attempt, so they’re stuck down.” And in a way, Morris, the male prostitute is in some ways the conscience of the book.

Actually, just as an aside, Penelope Fitzgerald said that he was based on a real person who she really liked who actually committed suicide in real life, but she didn’t want to have that in the book because she couldn’t bear to do that to this guy. So this is the Maurice that should have been, but he speaks what are called sombre truths and one of them is “decision is torment for anyone with imagination.”

Jo Hamya:

Yes. I did like that line a lot.

James Walton:

So there’s half-and half-people, “creatures neither of firm land nor water,” as I say.

Jo Hamya:

So that’s Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald, winner of the 1979 Booker Prize. And now, we’re going to switch gears slightly and move to-

James Walton:

You say slightly.

Jo Hamya:

… move to a book from the International Booker Prize, Boulder by Eva Baltasar, translated by Julia Sanches and shortlisted in 2023, which was of course the year that Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodino and translated by Angela Rodel won - friend of the show. You can listen to our interview with him from about the end of last year.

James Walton:

Both of them.

Jo Hamya:

Eva Baltasar is actually the first Catalan writer to be shortlisted for the International Booker Prize. She’s the author of 10 collections of poetry and 3 novels, and the book actually has echoes of her own life, so the premise is actually incredibly simple.

Boulder, so named by her partner, Samsa, is a woman from Barcelona and a cook on a merchant ship. She meets Samsa while docked in southern Chile where the two begin a really intense sexual and emotional relationship, albeit somewhat long distances as they have to wait for Boulder;’s ship to dock before they can meet. We’re going to play you a short clip of Michelle de Swarte’s reading from the book because I don’t think I can do justice to quite how central it is, but you need to know to get an idea of the book. So here’s the clip.

Michelle de Swarte:

“It’s 5:00 in the evening. It’s already dark out. I hold a coffee, drop my bags on the floor and make my way to one of the few seats available next to a pair of towniers and a boy busy dunking his fingers in the tea. She’s at a table in the back with 5 or 6 other people, white blonde hair, swimming shoulders.

I can’t not look at her like when you peer over the edge of a boat and come face to face with a shark. I forgot to add sugar in my coffee. I burn my tongue. I feel the hardness of the rock in which desire has become lodged as if for all time. I look at her and she fills every corner of me. My gaze is a rope that catches her and draws her in. She looks up, sees me. She knows. We spend the night together. I drink her like I’ve been raised wandering the desert. I swallow her as if she were a sword, little by little and with enormous care.”

Jo Hamya:

And so eventually, once they’ve been together for a while, Boulder agrees, at Samsa’s request, to settle into domestic routine in Reykjavik, very different country, where the latter has gotten a job. Domestic life really doesn’t sit well with Boulder, but she tries to make the best of it, that is, until Samsa decides that she wants a baby. I’m just going to read how bolder responds to this.

“I tamp down the truth and say, all right, let’s do it. I don’t tell her that what I want is not to be a mother.” From there what we get is essentially the breakdown of the relationship over what is usually regarded as the very thing all serious couples should be striving for. It’s a really, really, really small 105-page book. It’s deeply central, but I don’t think you can underestimate the extent to which, for all its sensuality, the text really rigorously applies itself to the project of dismantling the linguistic and emotional associations between the words “mother” and “woman” and cleaves them completely apart, so that what you have essentially is Boulder learning how to accommodate the care she feels for her eventually lovely daughter, Tinna, without considering herself… or I guess it wouldn’t be daughter then… without considering herself a mother.

James Walton:

Yes, all that you say is absolutely true, but Boulder herself is a terrific character because she’s not in the least bit ingratiating, is she? Sort of the opposite. It’s also very good on just the practicalities of how the pregnancy happens and when it first happens, her first thought is, “Oh no, I won’t be able to smoke inside anymore.”

In a way, I suspect some men will recognise she’s feeling the unwanted partner. She realises she’s slightly beside the point now, now that the mother and child are together and she’s also resentful as well. So she’s resentful that she feels slightly betrayed, in a way, that Samsa has gone off with another person, which is the baby.

It’s also sometimes quite funny, again, things that parents will recognised when they move into a bigger place when the baby’s 2 months old and they move their own little stuff, but the baby’s absolutely got tonnes of clutter with her. And she says, “Two months isn’t nearly enough to have hoarded so much wealth.” In fact, she’s quite, in a way, almost a bit of an old school bloke. Well, in the sense there’s one bit where she says, “When I put her in a place, she turns on the waterworks.” And she also goes out, boozing, eyeing up other women.

And then, she eventually picks up another woman called Anna, and then reflects later. “It takes three months to exhaust all interest in her body. I leave Anna the way I picked her up without stopping to wonder if there might be a real person inside.” As I say, not ingratiating, but yet somehow likeable. But when they decide to go for the home birth, she thinks, “Well, that’s a mistake, but then I’m not the one who’s going to be losing buckets of blood.” Her attitude to the baby itself is mixed because she does sort of love the baby.

Jo Hamya:

Well, I think you’re underselling it in a way because one of the reasons you still like Boulder is because in spite of the fact that she doesn’t want to be a mother, she still has a really beautiful relationship with Tinna, the child, that is wholly separate to the weird parasitic relationship that Samsa has with the child.

So there’s this gorgeous passage that goes, while Boulder is taking care of Tinna, “When she sleeps nuzzled up against me like this, eyes flickering behind her eyelids, I feel as if life is facing up to me and saying, ‘The time has come for me to believe and let my guard down.’ When she wakes, I freshen her up, change her clothes, make her some baby food. She loves listening to the radio. She treats me to a performance that she never puts on in front of Samsa. She scoots around the kitchen on her butt, bumping along as she whistles like a kettle and glancing up at me all laughter and drool. This is her way of asking for the radio to be turned on, or at least I think it is because the minute I do, she gets down on all fours and scurries over to me. Then I take her in my arms and we dance.

I’m a terrible dancer. I have no sense of rhythm or any interest in moving my body in sync with another except during sex, but a baby’s willpower is one and whole. It knows exactly how to build everything up and tear it all down, how to make mountains and raise them to the ground. So I do something I never have with Samsa. I hold Tinna’s body to me and explore the intimacy that wells up when the world closes around us. We dance.” That’s a beautiful relationship.

James Walton:

Two things on that, when you’re saying she doesn’t want to be a mother, she surely obviously doesn’t want Samsa to be one either. But that bit, I wonder. As you read on, I’m beginning to lose faith in this, but that phrase, “When she looks at me, I feel as if life is facing up to me and saying, ‘The time has come for me to believe and let my guard down.’” Now in most books, that would be a moment of glorious redemption, but in this book, is it possible that that’s slightly horrifying being asked to let her guard down? Because letting her guard down is something she never wants to do.

There’s a bit like that later where she’s talking about the baby and says, “It’s like she’s letting out a stream of light that lifts all the ugliness from the world. I had no idea a child could be such a huge obstacle.” So in a way, I think there’s still an ambivalence to being asked to let her guard down. The baby does that; baby is asking to let her guard down and that’s not a good thing to ask Boulder necessarily.

Jo Hamya:

Well, I don’t know. I think the way I’ve read this book is that the problem, Boulder’s problem, essentially, with Samsa is that Samsa is asking her to make too many binary choices. The way that Samsa operates is so weirdly heterosexual considering that it’s a gay relationship. It’s modelled on this really weird nuclear family principle that I’m not surprised that Boulder… She tries her best, but I’m not surprised that she just keeps… I really want to swear because this is such a… I know I can’t.

James Walton:

No potty mouth, Jo.

Jo Hamya:

But I’m not surprised that she keeps messing up.

James Walton:

Messing up. Okay, we get what the swear might’ve been. I like that it can be this in a way further along. I did see one interview with Eva Baltasar where she’s talking about how gay novels that she first read, they have to be about coming out because that was what they had to be. And this is so far beyond that now, isn’t it?

Jo Hamya:

Yeah.

James Walton:

Or it’s just much more, in a way, interesting and complicated and further on than that.

Jo Hamya:

So that’s Boulder by Eva Baltasar. And that pretty much concludes for short books that you can read in January and look deeply intellectual while only spending maybe about three hours total.

James Walton:

Three top Booker books under your belt and you’ve still got the rest of the weekend free.

Jo Hamya:

They are not the only short books in the Booker Library. We’ve been debating to what extent short books get shafted during the Booker Prize long listing and shortlisting process, but actually, when I think about it, there are a few that we’ve covered on this podcast. The Seed by John Banville and The Vegetarian by Han Kang come to mind. Those are great episodes if I do say so myself.

James Walton:

You are also a Moon Tiger fan, aren’t you then?

Jo Hamya:

I am.

James Walton:

That was another quite short winner, wasn’t it?

Jo Hamya:

That is quite a short winner. And you can visit thebookerprizes.com to see an interview that and our producer, John, did with Penelope at home about Moon Tiger.

James Walton:

That’s Penelope Lively, author of the Moon Tiger. I’ll mention a couple of short ones, which is both coincidentally, but rather pleasingly, well short-listed or long-listed the year that the winner was The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton, which is by far the longest ever book of winner. And one is The Testament of Mary by Colm Tóibín, quite different from his other books. This is Mary as in mother of Jesus with a alternative view of her life, but comes in at a pithy 96 pages. And long-listed that same year, The Spinning Heart by Donal Ryan who… This was his debut and he’s establishing himself more and more with every book, I think.

This is a book set just after the Celtic Tiger thing had collapsed and as familiar from readers of The Bee Sting by Paul Murray - last year, shortlisted. And this is an amazing kaleidoscope of different voices from the same small Irish town reflecting on what that all means. Again, funny and tender and great and, again, won’t take up much of your time.

Just to remind you, there are three short books for your Booker hack today were Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These, Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore and Boulder by Eva Baltasar translated by Julia Sanches. We’re back next week with the Burns Night special in which we are going to be discussing the all-conquering, much-loved Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart.

Jo Hamya:

That’s it for this week. Remember, you can watch the extracts from Boulder and Small Things Like These on our YouTube channel, and I really, really, really recommend the one from Boulder.

James Walton:

And you can also follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Substack at The Booker Prizes.

Jo Hamya:

Until next time, bye.

James Walton:

Bye.

Jo Hamya:

The Booker Prize Podcast is hosted by me, Jo Hamya, and also James Walton. It is produced and edited by Kevin Meola and the executive producer who’s John Davenport. It is a Daddy’s Super Yacht production for the Booker Prizes.