Podcast

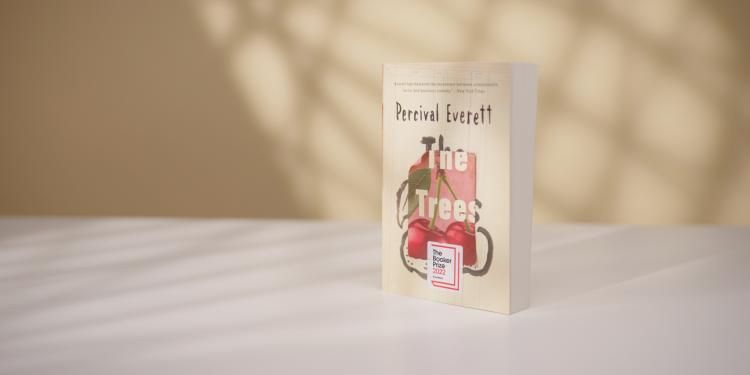

Explore Percival Everett’s Booker Prize 2022 shortlisted novel The Trees with your book club using our guide and discover why the judges said it ‘asks questions about history and justice and allows not a single easy answer’

Download a PDF of the reading guide for your book club

Something strange is afoot in Money, Mississippi. A series of brutal murders are eerily linked by the presence at each crime scene of a second dead body: that of a man who resembles Emmett Till, a young black boy lynched in the same town 65 years before.

The investigating detectives soon discover that uncannily similar murders are taking place all over the country. As the bodies pile up, the detectives seek answers from a local root doctor, who has been documenting every lynching in the country for years…

A violent history refuses to be buried in The Trees, which combines an unnerving murder mystery with a powerful condemnation of racism and police violence.

The Trees by Percival Everett

Percival Everett is the author of over 30 books since his debut, Suder, was released in 1983. His works include I Am Not Sidney Poitier, So Much Blue, Erasure and Glyph. He lives in Los Angeles and teaches at the University of Southern California. Everett was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2020 with his novel Telephone. He received the Ivan Sandrof Lifetime Achievement Award at the National Book Critics Circle Awards 2022.

Percival Everett, author of The Trees

© Nacho GobernaIn a nutshell

Part southern noir, part something else entirely, The Trees is a dance of death with jokes - horrifying and howlingly funny - that asks questions about history and justice and allows not a single easy answer.

On the characters

Ed and Jim, the Special Detectives (‘And that’s not just because we’re Black,’ Jim said. ‘Though plenty true because we are.’) are sent to investigate an uncanny murder in Money, Mississippi - a classic cop double-act with a nice line in deadpan jokes.

On the book

Everything about The Trees is relevant to today’s world. Everett looks at race in America with an unblinking eye, asking what it is to be haunted by history, and what it could or should mean to rise up in search of justice.

It’s an irresistible page-turner, hurtling headlong with swagger, humour, relish and rage.

The New York Times:

‘Humor may seem ill-placed in a novel about lynching, but Everett has mastered the movement between unspeakable terror and knockout comedy, so the reader covers a laughing mouth with one hand and stifles a gasp with the other.’

The Telegraph:

‘The theme of The Trees is the iniquity of the lynchings that proliferated in the American South for much of the 20th century - perfect material for a heart-rending indictment of endemic racism. But instead of a soulful historical novel that the white reading public could buy in droves in order to feel invigoratingly ashamed, Everett has produced a mixture of zombie horror, detective story and Tom Sharpe-esque farce, making comedy out of subject matter so inappropriate that this reader started looking round nervously in fear that my barks of laughter might be taken down and used in evidence against me.’

The Guardian:

‘The genius of this novel is that in an age of reactionary populism it goes on the offensive, using popular forms to address a deep political issue as page-turning comic horror. It’s a powerful wake-up call, as well as an act of literary restitution.’

The Times:

‘What a joy that Percival Everett has been included on this year’s Booker prize longlist for The Trees; it’s about time this extraordinary American writer, aged 65, got some credit this side of The Pond. Satire is most often the name of Everett’s game - he spins bracing, sideswiping comedy out of his country’s most divisive issues. You never know quite what you’re going to get with one of his novels, but one thing you’re guaranteed to find is a gleeful mucking-about with genre conventions.’

NPR:

‘With a highwire combination of whodunnit, horror, humor and razor blade sharp insight, The Trees is a fitting tribute of a novel: hard to put down and impossible to forget.’

Is the book a crime novel, or a parody of a crime novel?

Granny C is based on Carolyn Bryant, the woman who was partly responsible for the real-life lynching of Emmett Till in 1955. ‘Well, it’s all done and past history now, Granny C,’ her daughter-in-law tells her. ‘So you just relax. Ain’t nothing can change what happened. You cain’t bring the boy back’ (p. 16). Everett uses foreshadowing in this early scene to show that you can’t outrun your past and how trauma is inescapable even though it is now ‘history’. Discuss the flippant attitude of Granny C’s daughter-in-law and why Granny C is revisiting her actions at this point in time.

At one point, two of the black officers investigating the murders are asked why they joined the police force, to which they reply: ‘So Whitey wouldn’t be the only one in the room with a gun’ (p. 148). Discuss the significance of this statement with regard to the novel, but also real-life, modern police violence in the US.

In one of the more affecting parts of the novel, Damon Thruf hand writes the name of every lynching victim in the US in pencil. He says he will later erase them to ‘set them free’ (p. 211). The novel ends with him determinedly typing more names out on a typewriter. Why has he not - as he said he would - erased them? What is the meaning of this final scene, and Mama Z’s final line?

Ed and Jim stop at The Bluegum restaurant for some food, where the clientele is almost exclusively Black (p 246). The song Strange Fruit, made famous by Billie Holiday, starts playing. What is the significance of this song and how does it intertwine with Everett’s narrative?

The Guardian said of The Trees, ‘As with the films of Jordan Peele, the paranormal is used to depict the African American experience in extremis, and here supernatural horror and historical reality collide in dreadful revelation.’ Is it fair to describe Everett’s novel as conventional horror? How does it blur the line between the realities of real-life horror and the more fantastical?

Everybody talks about genocides around the world, but when the killing is slow and spread over a hundred years, no one notices. Where there are no mass graves, no one notices. American outrage is always for show. It has a shelf life. (p. 318). Discuss this quote in relation to Black history in America and how racism has allowed lynchings and killings of Black people to continue to happen.

‘And they used to have cross burnin’s a lot more and family picnics and softball games and all such,’ said Donald. ‘I remember eatin’ cake next to that glowing cross. I loved my mama’s cake.’ ‘Yeah,’ several voiced their agreement. ‘We don’t do nothin’ now,’ a man complained. ‘I don’t even know where my hood is. I don’t even own a rope.’ (p. 110). Everett often makes a pointed display of the rose-tinted nostalgia of white supremacy through caricatures of the white community in Money, Mississippi. Donald Trump even features in the novel. Is it fair to say The Trees is a novel of the Trump era?

The author uses humour throughout the text, from wordplay to punchlines and even slapstick gags. How does this use of humour within harrowing subject matter help readers navigate this material?

The Trees has extremely short but impactful chapters (sometimes less than a page long in length) that constantly shift in perspective. Discuss the benefits of a narrative structure like this - does it allow the reader to experience a breadth of viewpoints?

‘There’s a reason that oppressive regimes often resort to burning books. No one can control what minds do when reading; it is entirely private. We make of literature what we need to make. This is true of art. This is why the fascist right-wingers are so invested in a populace that is under-educated. For example, the Republican Party of my country would rather instruct someone to be proud that

they completed fifth grade than disappointed that they didn’t make it through sixth. This while they thrive on expensive educations from good schools. There is nothing more challenging to an oppressive government than a populace that can read, and therefore think.’

Read more of Percival Everett’s interview on the Booker Prize website.

Percival Everett

© Dan Tuffs/AlamyBorn in July 1941, Emmett Louis Till was a 14-year-old African-American boy who was murdered by lynching in 1955.

Emmett was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi during the summer of that year. He stayed with his great uncle and spent his days helping with the cotton harvest. Accounts vary, but while there, he visited a local grocery store and allegedly said something flirtatious to the woman behind the counter - Carolyn Bryant - while in the shop. This small action triggered Roy Bryant, Carolyn’s husband, and J.W. Milam, Bryant’s half-brother, to abduct Emmett on August 28.

The men beat and tortured the boy, gouging out his eye. He was taken to the Tallahatchie River, where he was shot in the head. Bound in barbed wire, he was dumped in the river where he was found, three days later, unrecognisable. Emmett’s murderers were arrested and charged, but were later acquitted by an all-white and all-male jury.

At Emmett’s funeral, his mother chose to keep her son’s casket open, to ensure the rest of the world witnessed the horrors inflicted upon her son by his murderers. Shortly afterwards, the defendants sold their story revealing the details of the murder to a journalist. The nation, and the world, were horrified and Emmett’s murder became a key moment in the civil rights movement, highlighting racial injustice and violence towards Black people in America.

Emmet Louis Till with his mother

© Chicago Tribune file photo/TNS/Alamy Live NewsDetail on the murder of Emmett Till from History.com

The Atlantic long read on Emmett Till

A timeline of the civil rights movement

A history of lynching in America

The Blood of Emmett Till by Timothy B. Tyson (non-fiction book)

Percival Everett, I Am Not Sidney Poitier

Percival Everett, Erasure

Paul Beatty, The Sellout

Chester Himes, If He Hollers Let Him Go

Chester Himes, A Rage in Harlem

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God