Book extract

Explore NoViolet Bulawayo’s Booker Prize 2022 shortlisted novel Glory with your book club using our guide and discover why the judges said it was ‘a magical crossing of the African continent’

Download a PDF of the reading guide for your book club

A long time ago, in a bountiful land not so far away, the animals lived quite happily. Then the colonisers arrived. After nearly a hundred years, a bloody War of Liberation brought new hope for the animals - along with a new leader: a charismatic horse who commanded the sun and ruled and ruled - and kept on ruling…

Glory tells the story of a country trapped in a cycle as old as time. And yet, as it unveils the myriad tricks required to uphold the illusion of absolute power, it reminds us that the glory of tyranny only lasts as long as its victims are willing to let it. This energetic and exhilarating joyride from NoViolet Bulawayo is the story of an uprising, told by a vivid chorus of animal voices that help us see our human world more clearly.

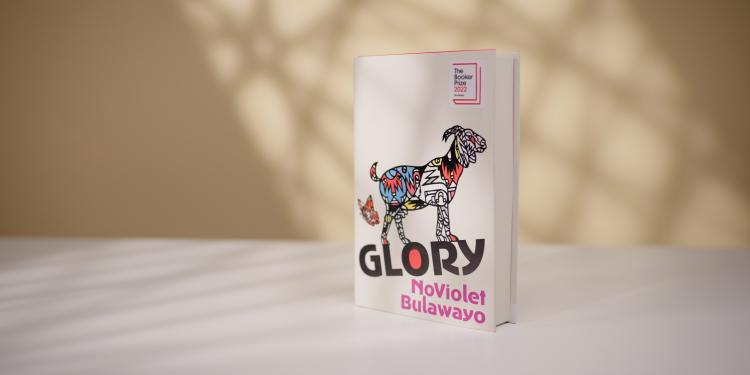

Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo

NoViolet Bulawayo’s debut novel, We Need New Names, was shortlisted for the 2013 Man Booker Prize and Glory was shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2022. We Need New Names was also shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award and the Barnes & Noble Discover Award, and won a Betty Trask Award, Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award, Hurston-Wright Legacy Award, the Etisalat Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction.

Bulawayo has also won the Caine Prize for African Writing and a National Book Award’s ‘5 Under 35’. She grew up in Zimbabwe before moving to Kalamazoo, Michigan, at the age of 18. She earned her MFA at Cornell University, and was a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, where she taught fiction. She currently writes full-time, from wherever she finds herself.

NoViolet Bulawayo

© Nye' Lyn ThoIn a nutshell

Glory is a magical crossing of the African continent with its political excesses and its wacky characters. Here, the fable is never far from the reality.

On the book

This political satire goes beyond Zimbabwe and could relate to nations with despotic regimes around the world. It is also a book about feminism and power sharing.

On the characters

Destiny is one of the most unforgettable characters of Glory. She has returned to Jidada from a long exile. She witnesses the tumult, the revolution in the country and how the women are fighting against the regime. She is the symbol of the young African women in the continent. The other unforgettable character would be the Old Horse, as it inevitable to see behind him the despotic president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe. The Old Horse has a strange cabinet: a Minister of the Revolution, a Minister of Things, a Minister of Nothing, and so on.

The New York Times:

‘…by aiming the long, piercing gaze of this metaphor at the aftereffects of European imperialism in Africa, Bulawayo is really out-Orwelling Orwell. This is a satire with sharper teeth, angrier, and also very, very funny.’

Financial Times:

‘Glory is a memorable, funny and yet serious allegory about a country’s plight under tyranny and what individual and collective freedom means in an age of virtual worlds and political soundbites.’

The Scotsman:

‘The ending is redemptive and given how closely it limns to Zimbabwean contemporary history, the closure has to be fictional. It is brave, and moving, as the citizens learn, slowly, to be unafraid. Bulawayo invites you to suspend disbelief in order that you believe.’

The Guardian:

‘Bulawayo leans into exaggeration and irony to tell hard truths. Glory is jam-packed with comedy and farce, poking fun at an autocratic regime while illustrating the absurdity and surreal nature of a police state.’

The Washington Post:

‘Bulawayo shifts among omniscient narration, first-person plural, oral history and even chapters written as Twitter threads. The effect can be disorienting, but individual voices stand out.’

Glory is a satirical take on Zimbabwe’s 2017 coup and the fall of Robert Mugabe, which the author has chosen to narrate through anthropomorphised animals. Why do you think Bulawayo chose to write the novel as a fable?

Aside from its ties to modern Zimbabwean history, the novel is laced with cultural hot takes. Those last three words we’ve heard said over and over by Black American brothers begging killers for their lives in the simplest, most desperate of prayers - ‘I can’t breathe’. (p. 206) is a reference to George Floyd’s death and cries to ‘make Jidada great again’ echo the political rallying of the Trump campaign. What other devices does the author use to make this a novel of our times? Does its timeliness make Glory more compelling?

Glory draws heavily on George Orwell’s Animal Farm but the author has leveraged her knowledge of African folklore and oral storytelling, too. Where do you see these influences intersecting within the novel?

While the book has traditional segments that are akin to chapters, its structure more closely resembles a series of vignettes, with headings and subheadings within. Did this guide or inform your reading experience any more than a traditional narrative structure? How does it serve the story?

Glory is narrated through a chorus of different voices and can be read as a polyphonic novel. Does this narrative technique offer a broader range of perspectives from the collective inhabitants of Jidada?

The Booker judges said Destiny ‘is the symbol of young African women on the continent’ and called her ‘one of the most unforgettable characters’ within the story. Why do you think Destiny returned after exile? What has instigated her return?

Jidada operates an oppressive patriarchal system and the females are routinely treated as second-class citizens. Discuss the parallels between their treatment in the novel and the world we currently live in. What countries and communities do you see the author drawing inspiration from?

A swarm of red butterflies recurs within the story. What do you think the butterflies signify, and what do the citizens of Jidada see in them?

According to the Guardian, ‘The stylistic use of the refrain “Tholukuthi”, meaning “only to discover”, nods to a social media moment. Around the time of the Zimbabwe coup, the song Tholukuthi Hey! was released, and once it went viral, the refrain became a meme.’ Discuss how the repeated use of the word serves both as incantation and a form of punctuation, and the extent to which it helps the novel to appeal across generations.

Discuss the following excerpt from the text and the point the author is making about personal complacency within a regime. (p. 271). ‘’I know,’ Destiny said. But what she was thinking was that this was essentially the problem with Jidada - the impulse to normalise the Seat of Power’s mediocrity; tholukuthi the willingness of citizens to get used to that which should have otherwise been the source of outrage. So that the Seat of Power in turn normalised the docility of the citizens and continued what was no less than defecating on their heads. She kept her thoughts to herself, however, reached for the remote control, and turned the TV on.

‘Animals gave me the distance from a public drama that was often unfolding and changing shape as I was writing it (first as a work of non-fiction), and that understandably attracted so much attention it felt I was in a kind of weird competition with different commentators.

‘The animal kingdom freed me to make the story mine, deliver it on my own terms, with as much (at least, one hopes) freshness, inventiveness and madness as I dared bring on board. I must say the mind-blowing absurdity of Zimbabwe’s politics also made the choice the right fit, certainly the terms of reference by my frustrated countryfolk on social media suggested the same and influenced some of my choices.’

Read more of NoViolet Bulawayo’s interview on the Booker Prize website.

NoViolet Bulawayo

© David Levenson/GettyMugabe’s ascent to power began during the Zimbabwean Civil War of 1965-1980. He was the leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union, a political group focused on ending colonialism within the country. At the time, Mugabe was a hero.

Zimbabwe attained independence in 1980 and Mugabe became the country’s first democratically-elected leader. But over time, Mugabe became blinded by power. Zimbabwe began to experience economic decline in the mid-1990s with political and economic mismanagement at the heart of this problem.

Mugabe promised land redistribution to his black citizens, reclaiming land from the country’s white inhabitants, but, while this did happen, there was corruption within his policies. Mugabe’s personal fortune and wealth began to visibly display the tyranny with which he ruled.

In 2000, Mugabe lost his first major election yet refused to step down. Instead, his political rivals and their supporters were attacked and many were murdered, abducted and displaced during a time that is now renowned for state-organised violence. In the following elections, Mugabe turned to bribery and vote rigging to maintain his political standing.

In 2017, the dictator was forced to resign from his post after a military coup overthrew him, which called for his impeachment. He had been in power for 37 years.

Demonstrators on the streets of Harare, Zimbabwe, during the military coup, November 2017

© Christopher Scott/Alamy Live NewsAn overview of the rise and fall of Mugabe

New York Times feature on Mugabe

A history of Zimbabwe, detailing its colonialisation

NoViolet Bulawayo interview in the Guardian

The Fear: The Last Days of Robert Mugabe (non-ficton book)

NoViolet Bulawayo, We Need New Names

Amadou Kourouma, Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote

George Orwell, Animal Farm

Zadie Smith, The Embassy of Cambodia

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Half of a Yellow Sun