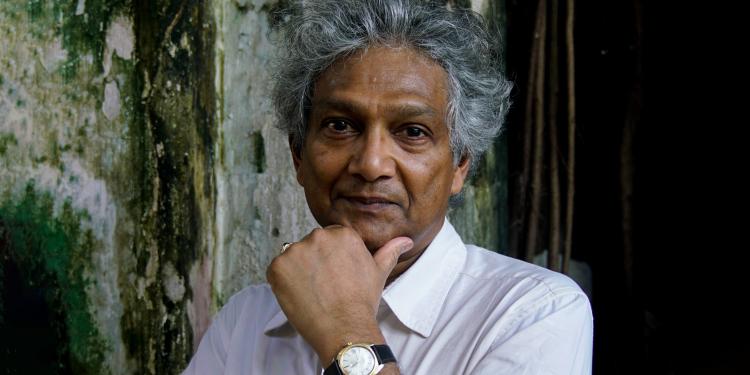

Meet the International Booker Prize 2024 judges: Romesh Gunesekera

Author Romesh Gunesekera talks about how his Sri Lankan childhood made him a reader and why the literary canon must diversify

Romesh Gunesekera is internationally acclaimed for fiction that explores key themes of our times – political, ecological, economic - through novels and stories of wide appeal that spotlight the complexities of people’s lives and the choices they are forced to make. His ten books include Reef, shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1994, with his work having been widely translated and he has won numerous prizes for his fiction including a Premio Mondello (Italy). He was the Chair of the judges of the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2015 and has also judged Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists (2013), the Caine Prize and the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award among others. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Why do you think the International Booker Prize matters, and what’s special or unique about it?

Fiction matters. Translated fiction has been a large part of the world that fiction creates. Fiction without Tolstoy, Flaubert, Borges is hard to imagine. Contemporary translated fiction continues to expand our imaginative world.

Tell us about your reading habits under normal circumstances. What type of books are you usually drawn to?

Since my twenties, most of the time, my reading has been governed by my writing. Either reading fiction that relates to what I am writing, or fiction that is as far away from my fictional world and its challenges as possible. Before that I relied on serendipity. In recent years, judging prizes has been a wonderful way of discovering unexpected pleasures.

Tell us about your path to becoming a reader. What did you read as a child? Was there a book or author that made you fall in love with reading?

My childhood was in Sri Lanka. TV had not arrived. To escape the everyday world, you had to rely on your own imagination fuelled by stories told or read, and outings to the cinema. The bookshops were not child-friendly and were dominated by that curious range of international bestsellers no one remembers any more. I relied on second-hand booksellers where you could part-exchange books and rushed my way through all the children’s series of the time: adventure books, western, war comics, superheroes and then those adult books that were rumoured to be x-rated in some way. The classics never featured, but the road from Enid Blyton to Henry Miller was a wild and exciting one where the point of reading was to be in a world that was completely unlike the one I was in. Relevance and familiarity were not what I wanted or needed. Sri Lanka made me a reader, but the Philippines, where I moved to as a teenager, made me a writer. There I discovered the American Beat Generation – writers for whom writing was in itself the thing to celebrate. Both these worlds, including the bookshops, you will find in my own novels.

What are you particularly looking forward to or already enjoying about the process of judging the prize? Has anything surprised you so far?

Opening my eyes to new worlds and different ways of making novels. I am already surprised at how much the form of the novel can be redefined, but I am also surprised at the similarities I have found across languages and countries. As a writer it is easy to believe you are writing on your own and forging a path no one has been on before. But we are all working with similar material and similar tools and our influences are not so separate. You may think you are heading for an island no one has ever been to before, but when you reach your destination you discover another writer, from another continent, has made the same journey. Turns out being novel may not be the most important element of a novel.

Romesh Gunesekera

AlamyWhat are you hoping to find in selecting books for the International Booker Prize longlist? Are there certain qualities or attributes that you’re looking for?

I hope I can be open to the books and hear them when they speak to me.

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

The canon is what we make of it. If it doesn’t diversify, and if it isn’t inclusive, it will ossify and become moribund. To encourage readers, we need to provide a feast for all tastes and make the books easily available. We also need to bring them into the centre of our conversations. Hearing my father and his friends talking wildly and excitedly into the night about Shelley and Dickens made me think there was something special there. It made me want to be a reader and then a writer.

A 2023 report commissioned by the Booker Prizes showed that, in the UK, under-35-year-olds account for almost 50% of all translated fiction sales. What do you think draws this younger readership to fiction from around the world?

I would love to know. I guess it must be because the world for them is smaller than it used to be. William Blake saw the world in a grain of sand. Today you see it on a screen in the palm of your hand. Perhaps it makes you want to know more. Fiction has always been news from some place of the imagination you didn’t know existed. The draw perhaps is the potential for discovery. Plus, at long last, new translated fiction is more easily available thanks to a blossoming of many new enthusiastic publishers.

Reef by Romesh Gunesekera

I hope I can be open to the books and hear them when they speak to me

— Romesh Gunesekera, International Booker Prize 2024 judge, on reading for the prize

In recent years, translators and their working relationships with authors have become more visible. Why do you think it is important to shine a spotlight on this role?

They have been the unsung heroes. So, it is time to sing their praises. A good translator makes all the difference.

What does the future look like for translators with the broader trend of AI and machine-led alternatives displacing workers? Could a bot ever replace a human translator of fiction?

I am sure a bot will replace authors of a certain kind of genre book. I remember inventing a vending machine for personally tailored fiction in a dystopian novel (Heaven’s Edge). But by the time I got to the next draft, it did not seem so far-fetched and so I removed it. That was twenty years ago.

Finally, what are your top three favourite works of fiction in translation that you would recommend to readers of the Booker Prizes, and how have they influenced you?

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

When I first read this book, I thought I was the only one in England to have discovered it. I didn’t realise magic realism was going to be one of the biggest waves in fiction. It is perhaps the book that has been most influential on me as a writer, when starting out, and possibly the least apparent in my own writing. This is a novel that shows how a world is made with words.

The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann

I read this novel relatively recently, although it has been on my shelves for years. A mountain, as it were, that waits for you until you are ready for it. Having eventually got there, I still feel I am there.

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Another big book that was a long time moving from my I-must-read-this-one-day shelf to I-have-read-this-and-I-am-amazed shelf, as Calvino would put it. Utterly compelling. I’ll never forget reading it. Partly because of the world of the book, but also because I read it in a weirdly appropriate week while waiting to be called into court on jury service – and I don’t mean a prize jury!

One Hundred Years Of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez