Book recommendations

Reading list

Following the death of the 1981 Booker-shortlisted author, Lucy Scholes reflects on Schlee’s life and body of work, which is resonating with a younger generation of readers

Ann Schlee, the American-born writer who spent most of her life in England, died last month aged 89. Praising her work in an essay in Slightly Foxed in 2004, the writer Jane Gardam declared that Schlee’s historical novels ‘are more advanced, more interested in feminism, for instance, than her contemporaries who write of the twentieth century’. Nowhere is this more evident than in Schlee’s masterpiece, Rhine Journey, which was shortlisted for the 1981 Booker Prize.

Set in 1851, it’s the seemingly modest story of a middle-aged spinster’s Damascene moment while accompanying her brother and his family on a European pleasure cruise. The Reverend Charles Morrison is a pious man of the cloth used to lecturing his flock. His wife Marion is a sickly and somewhat spoilt woman who, although not purposely cruel, is used to having her own way. Also included in the party is their 17-year-old daughter Ellie, chafing at her childhood, impatient to wear her hair up and fall in love.

Between her and her Aunt Charlotte, there exists a certain sympathetic intimacy, but the older woman is never allowed to forget her lowly position in the party. ‘The luggage has simply been left on the deck […] I had thought, Charlotte, that you were with it,’ chides Charles in the novel’s very first line, making it immediately clear that she – a living, breathing piece of baggage; her passage ‘generously paid’ by her brother – must thus always be prepared to make herself useful.

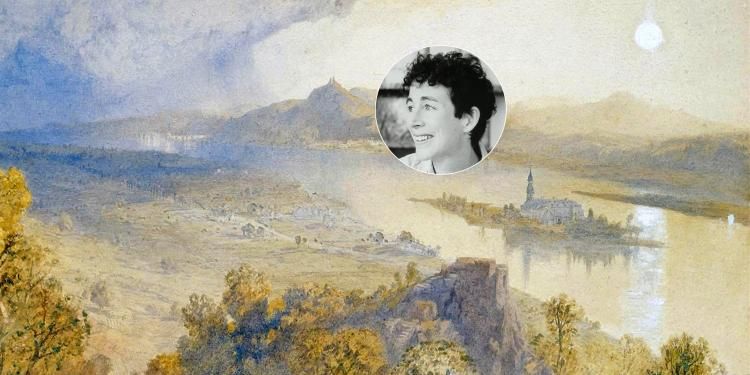

Ann Schlee

© Jerry BauerCharlotte isn’t one of those female figures we’ve begun to see in a certain kind of more recently written historical fiction; a woman whose sensibilities resemble that of a 21st century heroine, but whose body is confined by corsets and layers of heavy cambric. Though deeply invested in her creation’s psyche – indeed, the complexities and complications of fraught interpersonal relationships lie at the heart of all of her novels – Schlee did not pen revisionist histories. As such, it’ll come as no surprise to discover that the deft authenticity of Rhine Journey’s historical detail was highlighted in every review it received.

‘The sense of period is beautifully sustained, and we are never allowed to step outside it,’ applauded Graham Hough in the London Review of Books. ‘Ann Schlee possesses a remarkable gift for enabling the reader to enter a past world, enlightened but unshackled by modern concepts and prejudices,’ extolled Isabel Raphael in The Times. While The Observer’s Anthony Twaite astutely declared it a novel that ‘escapes any accusation of being a pastiche Victorian piece, though its sense of time, place and tone is perfect.’

It’s this elegance that draws readers in, immediately immersing us in an environment that is entirely foreign, yet, because of the sleekness of Schlee’s world-building, somehow also instantly intelligible. The manoeuvre is so swift and subtle that before we quite realise it, Schlee has plunged us ever further, deep into Charlotte’s inner world. On the landing stage at Coblenz, she sees a face that she recognises, that of the man she was in love with back when she was a girl, but whom her family considered unworthy of the match. It is not her lost suitor, of course, merely someone who closely resembles him.

Nevertheless, ‘the long bandaging years were cruelly stripped away,’ and the painful awakening of Charlotte’s memories brings with them a passionate stirring of the long-dormant sensual and emotional landscapes within her. She tumbles into a state of intense and total dislocation in which fantasy and reality converge. Forced to reckon with both her past and her future, she also inadvertently misinterprets significant events unfolding in the present.

Rhine Journey by Ann Schlee

It’s this elegance that draws readers in, immediately immersing us in an environment that is entirely foreign, yet, because of the sleekness of Schlee’s world-building, somehow also instantly intelligible

— Lucy Scholes on reading Rhine Journey

As befits a novel in which a deep, throbbing body of water takes centre stage, a second storyline flows just beneath the surface, connected to the political and social background against which Charlotte’s much more intimate drama plays out. As Schlee informs her readers in the brief historical note that precedes the text proper, this is only three years after the 1848 workers’ revolutions that swept Europe, and the inhabitants of Rhenish Prussia have had their liberties curtailed by the increased powers the police have been granted, the censorship of the press, and the constraints placed on the Lutheran Church.

‘It is unlikely that the Morrison family were concerned or even aware of these events,’ Schlee adds shrewdly. ‘They had come for Marion’s sake, to take the waters at Baden Baden and to experience on their return a romantic Rhine composed mostly of the fruits of judicious reading and the play of their own imaginations.’ Having thus cleverly thrown her readers off the scent, when, at the end of the novel, these two streams collide, it makes for a much more powerful climax than this otherwise slim and unostentatious volume might suggest.

It’s easy to understand how Rhine Journey made it onto the Booker shortlist – an all the more remarkable achievement given that it was Schlee’s first book for adults (though she had published five novels for younger readers during the previous decade, culminating with The Vandal, which won the 1980 Guardian Prize for Children’s Fiction), and the calibre of the other novelists that she was up against. The 1981 shortlist included three formidable literary doyennes: Molly Keane (Good Behaviour), Doris Lessing (The Sirian Experiments), and Muriel Spark (Loitering with Intent), as well as three up-and-coming bright young things in D.M. Thomas (The White Hotel), Ian McEwan (The Comfort of Strangers), and Salman Rushdie (Midnight’s Children).

Conversely though, Rhine Journey’s greatest strength has probably also been its Achilles heel. Regardless of its jewel-like quality – the London Review of Books described it as ‘a patient and cunning representation of the intimacies of a repressed and wasted life,’ the New Yorker declared it ‘a finished work of art,’ and the Guardian, ‘a little period gem of feeling and clarity’ – Rhine Journey is a quiet book. The opposite, we might say, of the kind of fiction then in vogue, especially that being produced by the pack of lauded young British novelists, amongst whom both Rushdie and McEwan held prime positions. (And to be honest, if you are going to lose to any Booker winner, it might as well be Midnight’s Children, a novel that went on to be crowned the Booker of Bookers, the accolade awarded in 1994 to celebrate the prize’s quarter-century birthday.)

Ann Schlee in conversation with Salman Rushdie at the Booker Prize awards ceremony 1981

© The Monitor Group/Courtesy Oxford Brookes ArchiveBut this perhaps goes some way to explaining why Rhine Journey, along with Schlee’s other novels, all of which are also period pieces – The Proprietor (1983), which is set on the Scilly Isles in the 19th century; Laing (1987), the story of the real-life Scotsman who made an expedition to Timbuktu in 1848; and The Time in Aderra (1998), which concerns a schoolgirl in the 1950s who travels to Africa to visit her mother and stepfather, a colonial administrator, and draws on Schlee’s own teenage experiences on that continent – fell out of print fairly swiftly.

Yet when I came across a copy of Rhine Journey a couple of years ago, I was both charmed by the graceful meticulousness of its period detail, and excited by the discreet radicalism of Charlotte’s story. I think Schlee’s own grandson, the writer and lecturer Sam Johnson-Schlee, put it best himself when he wrote about first reading it – something he did only two years ago: ‘The novel is an explosive device. And it is a shock to realise that your grandmother is a bomb maker.’

Although the action of Rhine Journey is tied up in the specificity of both the time and place during which and where it’s set, the story itself is driven by the inner workings of Charlotte’s mind. Without ever ringing untrue to the period, it’s a tale of female rage and agency, exploring how someone who’s been disenfranchised for so long that they’ve lost much of their own sense of self, might go about salvaging what’s left of their identify and reclaiming it as their own.

Schlee’s Charlotte is both ancestor and descendant of the likes of Charlotte Bartlett, Lucy Honeychurch’s aunt and chaperone in E. M. Forster’s A Room with a View (1908); the titular heroine of Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes (1926), another spinster aunt who wrestles herself from the suffocating bosom of her brother’s family home; and Edith Hope in Anita Brookner’s Booker Prize-winning Hotel du Lac (1984).

View on the River Rhine by George Clarkson Stanfield (1828-1878)

© Artepics/AlamyThe novel is an explosive device. And it is a shock to realise that your grandmother is a bomb maker

— Schlee’s grandson, Sam Johnson-Schlee, on Rhine Journey

And, as Gardam was perceptive enough to point out two decades ago, Charlotte’s story has much to say about feminism, and in this, Rhine Journey also feels akin to acclaimed recent novels such as Hernan Diaz’s Booker Prize 2022 longlisted novel and Pulitzer Prize-winning Trust, and Lauren Groff’s Matrix and The Vaster Wilds – all of which stay true to their historical setting, while also illuminating the previously obscured stories of female characters trapped therein.

No one was more surprised by the new relevance of Rhine Journey than Schlee herself. It was unexpected but delightful, she said earlier this year – when both McNally Editions (where I’m an editor) and Daunt Books Publishing approached her asking to republish it – to learn that a novel she wrote over four decades ago resonated with a much younger generation of readers. Not that writing was ever the be-all and end-all of her life. She wrote the five children’s novels that she published by getting up at 5am and writing before her own four children woke up and had to be got off to school.

She also taught for many years. Initially, as a young Oxford graduate, at Rosemary Hall (now Choate) in Connecticut (the state in which she was born; her mother was American), then later, back in England, in various schools, tutoring school refusers, and at evening institutes. Even after she retired, and she and her husband, the artist Nick Schlee, had left London for Berkshire – to give him more freedom to paint – she continued to work with children, running a much respected and popular youth club at her local church.

Fittingly, Rhine Journey draws to a close with a final emphasis on young Ellie. Charlotte might have missed her own chance for marriage and companionship – ‘the bleakness’ of a life ‘without bells, without flowers, without the sharp patter of rice’ – but she’s determined that the same fate won’t befall her niece. Hope, or at least the possibility of it, lies with the next generation.

Rhine Journey is being reissued by both Daunt Books Publishing (UK) and McNally Editions (US) in June 2024.

Ann Schlee, 1991

© Courtesy Oxford Brookes Archive