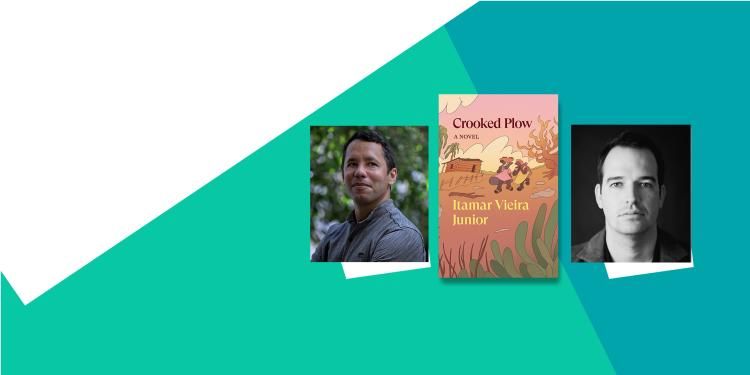

A Q&A with Itamar Vieira Junior and Johnny Lorenz, author and translator of Crooked Plow

With Crooked Plow longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024, we spoke to its author and translator about their experience of working on the novel together – and their favourite books

Crooked Plow was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024 on 9 April 2024. Read interviews with all of the longlisted authors and translators here.

Itamar Vieira Junior

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024, and what would winning the prize mean to you? Would it also have an impact on literature originating from your country?

I received the news of my nomination for the International Booker Prize with great enthusiasm. I’m the third Brazilian author nominated for the Booker in recent years, which is quite wonderful. The literature of my country has a very strong tradition, full of authors who’ve made a name for themselves beyond Brazil. If I were to receive the International Booker Prize, it would be a source of great pride for people in Brazil and help our stories reach new readers.

What were the inspirations behind the book? What made you want to tell this particular story?

I wrote Crooked Plow for many reasons, but if I had to choose just one, I’d say this: I wanted to bring to the page the love that Brazilian farmers feel for the land itself, for the earth of the Brazilian countryside.

How long did it take to write the book, and what does your writing process look like? Do you type or write in longhand? Are there multiple drafts? Is the plot and structure intricately mapped out in advance?

It took me about eighteen months to write the definitive version of the novel that would become known to the public. But the true origin of Crooked Plow occurred twenty years earlier; it was a story that stayed with me for two decades. In time, it would gain density and depth.

I wrote part of the story by hand (especially the first chapters). Later, I began developing the novel, typing away on my computer. But whenever I need to stop and reflect, I always return to writing by hand.

For me, to write is an experience of surprise – a surprise quite similar to that of reading. I never know in advance the path my story will take. I learn as I write, and this is why writing is so astonishing: human life, like literature, is unpredictable.

Itamar Vieira Junior

What was the experience of working with the book’s translator, Johnny Lorenz, like? How closely did you work together on the English edition? Were there any surprising moments during your collaboration, or joyful moments, or challenges?

The English translation process was a challenge. Of all the translations that the book has received, perhaps the translation into English by Johnny Lorenz was the one to which I dedicated the most time. Lorenz is a perfectionist and non-conformist; he is always looking for the word or phrase that will best express what the author wrote. He is not satisfied with easy solutions: he researches, writes, rewrites; he is not afraid to bother the author if it benefits the translation.

A number of questions arose during our discussions, but we’d talk and exchange bibliographies and even relevant photographs. From Lorenz I learned that the author does not know everything about the story: readers and translators will always illuminate obscure passages in the text.

Tell us about your reading habits. Which book or books are you reading at the moment, and why?

I’m writing my third novel, and I need to be immersed in language as a reader to be able to write well. The book I’m currently reading is Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments by Saidiya Hartman. These extraordinary women have inspired me to write my next story.

What was your path to becoming a reader – what did you read as a child and what role did storytelling play in your younger years? Was there one book in particular that captured your imagination?

Reading arrived quite naturally in my life. As I became literate, as I grew more fascinated with the world of literature, I began writing in order to reproduce the sensations that literature gave to me.

Children’s literature was crucial in helping me develop, early on, the habit of reading. I remember one book in particular, O caso da borboleta Atíria by Lúcia Machado de Almeida (an important Brazilian author of children’s books). This book, featuring insect characters, opened up an experience to me that transcended human life, my life.

From Lorenz I learned that the author does not know everything about the story: readers and translators will always illuminate obscure passages in the text

Tell us about a book that made you want to become a writer. How did this book inspire you to embark on your own creative journey, and how did it influence your writing style or aspirations as an author?

Dom Casmurro by Machado de Assis was the novel that solidified my interest in writing literature. I read it when I was 12 years old; I was captivated by the complexity of the book’s characters. And a novel that would renew my passion for writing was Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.

Tell us about a book originally written in Portuguese that you would recommend to English readers. How has it left a lasting impression on you?

Grande Sertão: Veredas by João Guimarães Rosa (translated as The Devil to Pay in the Backlands) – it’s an intricate novel that captures, in an original way, the Brazilian soul. Guimarães Rosa expands the horizons of the Portuguese language with an imaginative vernacular that also serves as an allegory for our immense cultural diversity.

Do you have a favourite International Booker Prize-winning or shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

The Vegetarian by Han Kang. It’s a cruel and inventive story written in an extraordinary manner. It’s one of those books that, even after so many years, we remember with the freshness of our first reading.

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

Translations allow stories to reach readers across diverse languages and help us appreciate the complexity of this world. I consider Beloved by Toni Morrison to be one of the most beautiful and important novels of the second half of the 20th century. Morrison was able to transform a woman’s dark crime into an act that any of us might have carried out in her situation. Literature has this magical ability to allow us to exchange roles; it’s an agreement we make as writers and readers: when reading – or writing – we live the lives of the characters, we peer into their most unfathomable secrets, and we recognize ourselves in the immensity of our own humanity.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Johnny Lorenz

How does it feel to be longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024 – an award which recognises authors and translators equally – and what would winning the prize mean to you?

Working to recreate the power and immediacy of the original text in my translation, I am trying, in some sense, to disappear. The translator is often an invisible presence. The International Booker Prize, however, brings a welcome visibility to the figure of the translator – and, of course, to brilliant novelists from around the globe. Literary translators spend so much time alone, moving between texts, contemplating the texture of an adjective, the nuances of a figure of speech, the weight of a noun; to now be part of this very public and joyful celebration of literature in translation is tremendously gratifying.

How long did it take to translate the book, and what does your working process look like? Do you read the book multiple times first? Do you translate it in the order it’s written?

I translated Crooked Plow over the course of three years. My first step was to get everything down in English, but the first draft of a chapter is like a shipwreck on the page. I return to it and keep returning; I tinker and fix and reassemble. Sometimes a hammer is needed, sometimes sandpaper. When things are going well, the translator can feel the energy shifting, and the mainsail fills with wind.

Aside from the book, what other writing did you draw inspiration from for your translation?

I found inspiration in the fiction of Raduan Nassar. A passage from his novel Ancient Tillage (translated to English by K.C.S. Sotelino) serves as the epigraph for Itamar Vieira Junior’s Crooked Plow. Nassar, incidentally, was longlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2016. My translation of Crooked Plow also found inspiration in Gabriel Banaggia’s book, As forças do jarê, an ethnographic study of Jarê, the African Diasporic belief system that features prominently in Crooked Plow. In all three of these books, the reader can almost smell the damp earth of the countryside; the stable and the wood-burning oven; the medicinal herbs.

Johnny Lorenz

What was your path to becoming a reader – what did you read as a child and what role did storytelling play in your younger years? Was there one book in particular that captured your imagination?

I was a child who attended Catholic school – so I grew up with stories of the flood; a woman transformed into a pillar of salt; a mystical trinity; leviathans and crowns of thorns. My most powerful memories of crafted language come from childhood recitations: a soliloquy from Macbeth I committed to memory, or the Peace Prayer of Saint Francis, even the lullabies and playful chants we knew as children. I recall a nursery rhyme from Brazil I’d learned from my mother, ‘Atirei o pau no gato.’ (Like many such nursery rhymes, there’s a violent edge to that one.) I suppose I’ve always been interested in the musical aspect of language – not just the words, but the syllables.

Tell us about your path to becoming a translator. Were there any books that inspired you to embark on this career?

When I was a teenager, during a trip to visit my family in Brazil, I received a gift from my vovó, my grandmother. It was a book by Mario Quintana, a very popular poet in Brazil. To my surprise, there were no English translations of his poetry. I figured I’d have to translate those poems myself in order to read them in English.

What are your reading habits under normal circumstances? Which book or books are you reading at the moment, and why?

I’ve just finished reading a wonderful book, Um rio sem fim (A River with No End), by Verenilde Pereira, an Afro-Indigenous writer from the Amazon region of Brazil. Her rather astonishing novel from the late 1990s has been more or less overlooked, but a new edition will be published soon in Brazil. (I’ve already begun translating it.) I’ve been reading the gorgeous poetry of Kaveh Akbar, because a very bright student of mine recommended him to me. I’m somewhere in the middle of The Love of Singular Men by Victor Heringer, translated by James Young. I’m reading John Keene’s Song Cave, too, which I was delighted to find in my local bookshop.

The first draft of a chapter is like a shipwreck on the page. I return to it and keep returning; I tinker and fix and reassemble

Tell us about a book originally written in Portuguese that you would recommend to English readers. How has it left a lasting impression on you?

I recommend reading Clarice Lispector. I’ve translated two of her novels, but here I’ll recommend a book I didn’t translate: The Hour of the Star, translated by Benjamin Moser. Lispector is the queen of the arresting phrase. Another recommendation: Dom Casmurro by Machado de Assis – a classic! A twisted and tragic love story from the 19th century. The gaps and silences and ellipses of this novel are just as meaningful as the words on the page.

Which work of translated fiction do you wish you had translated yourself, and what aspects of this particular work do you admire most?

Since we’re in the realm of wish-making and fantasy: The Book of Disquiet by Fernando Pessoa, beautifully translated by Richard Zenith. That book was a revelation. Zenith also translated the great poet João Cabral de Melo Neto; the poem ‘The Wind in the Canefield’ is a description of a landscape, and it’s almost unbearably moving to me, although I’m not sure why.

Do you have a favourite International Booker Prize-winning or shortlisted novel and, if so, why?

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell. It’s a book I’ve taught in my literature class at Montclair State University. As in The Turn of the Screw by Henry James, a child appears in this story, a boy who doesn’t seem quite right, a boy who frightens us. I love the way the book operates as a horror story; later we come to understand that the true horror of the story is something else entirely.

What role do you think translated fiction plays in promoting a more inclusive and diverse literary canon, and how can we encourage more people to read it?

My university students here in the U.S. often admit that they have never read, for example, a novel from Latin America, or any novel in translation, really. To promote fiction in translation (especially in our school systems) is urgently necessary – not only because this literature might offer a powerful aesthetic experience, but because it complicates the facile dichotomy of ‘us’ versus ‘them.’ One of the reasons why I teach a book like Signs Preceding the End of the World (written by Yuri Herrera, translated by Lisa Dillman) is precisely because this novel undermines the suffocating narrative of certain media outlets that immigrants (especially immigrants from Latin America) are ‘problems.’ Herrera’s novel introduces us to a young woman who crosses the border, and it gives us a chance to recognize how brave that woman is.

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin

- By

- Itamar Vieira Junior

- Translated by

- Johnny Lorenz

- Published by

- Verso Fiction